|

We love the 29th of the month—any month—because it’s National Gnocchi Day.

While the U.S. celebrates 14 pasta holidays, gnocchi is not one of them.

However, the 29th of every month is National Gnocchi Day in Argentina. We have no problem with that whatsoever!

Our gnocchi recipe this month is Gnocchi alla Sorrentina, which hails from the charming coastal town of Sorrento in southwestern Italy, on the Bay of Naples.

The recipe is below, but first: What is “alla Sorentina?”

> 14 more gnocchi recipes.

> The history of gnocchi.

> The origin of Gnocchi Day in Argentina.

> The history of pasta.

> The different types of pasta: a glossary.

> The difference between pasta and noodles, below.

WHAT IS “ALLA SORRENTINA”

“Sorrentina” refers to the style of cuisine popular in the area around Sorrento, highlighting local fresh ingredients: tomatoes, basil, olive oil, and mozzarella, often with a simple yet bold flavorful preparation that makes Italian cooking so good.

The best-known recipe may be Gnocchi alla Sorrentina, a classic dish of potato gnocchi baked in a rich tomato sauce with mozzarella and basil, baked until the top is golden and bubbly. It’s typically prepared in a terracotta dish.

Terracotta cookware (pignatta or tegame di terracotta) has been used for centuries in southern Italian cooking. It’s more affordable than metal, but also retains and distributes heat evenly, allowing for slow, even baking and keeping the dish warm after it comes out of the oven.

Other popular dishes from the area, topped with tomato sauce, mozzarella, and basil, and then baked, include:

Branzino alla Sorrentina, sea bass baked with cherry tomatoes, basil, olive oil, and sometimes mozzarella.

Melanzane alla Sorrentina, a variation of Eggplant Parmesan with tomato sauce, mozzarella, and basil but with fewer layers, and often garnished with roasted or fried eggplant.

Paccheri alla Sorrentina, large tube-shaped pasta (paccheri) that are sometimes baked with tomato sauce, mozzarella, and basil, and other times boiled conventionally and sauced on a plate.

Pollo alla Sorrentina, chicken breast or cutlets topped with tomato sauce, mozzarella, and basil (similar to Chicken Parmigiana but without breading).

Risotto alla Sorrentina, a creamy tomato-based risotto with melted mozzarella stirred in at the end for a rich, cheesy finish.

ARE GNOCCHI PASTA?

Good question! While gnocchi* are technically dumplings, they are listed on menus with the pasta because they are prepared in a similar way (boiled, baked) and served with similar sauces.

Traditional pasta is made from wheat flour, water, and sometimes eggs, while gnocchi are usually made from potatoes, flour, and sometimes eggs.

Pasta is often served al dente. The texture of gnocchi is also softer and more dumpling-like compared to traditional pasta.

> See the difference between pasta and noodles below.

RECIPE: GNOCCHI ALLA SORRENTINA

Make this dish with store-bought gnocchi. You can even use store-bought sauce, but the sauce in this recipe takes just 5 minutes to prepare, and is so much tastier than anything store-bought.

You can make the sauce ahead of time up to 3 days in advance and refrigerate; or make it as far in advnace as you like and freeze it. Heat it to a simmer before adding it to the baking dish.

Prep time is 5 minutes and cook time is 40 minutes.

You can use fresh gnocchi, which will cut the cooking time. Fresh gnocchi cook in 1 to 3 minutes. Dried gnocchi usually take 8 to 10 minutes. Either is ready when the gnocchi float to the surface.

Ingredients For 4-6 Servings

2 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil, plus more for coating

2 cloves garlic, minced

¼ teaspoon dried red pepper flakes

1 can (28 ounces) San Marzano-style crushed tomatoes

Sea salt

2 sprigs basil

1 ball (8 ounces) mozzarella, torn into pieces

1 box (16 ounces) potato gnocchi (or any other gnocchi—ricotta, pumpkin, etc)

1/2 to 1/3 cup freshly grated Parmigiano-Reggiano

Optional garnish: more red pepper flakes for heat, fresh herbs for brightness (basil, oregano, parsley, thyme)

Preparation

1. HEAT the EVOO in a sauté pan over medium heat. Add the garlic and cook until it begins to sizzle and release its fragrance. Stir in the red pepper flakes, then add the tomatoes and a pinch of salt.

2. BRING the sauce to a boil, then lower the heat to medium-low. Let the sauce simmer gently until thickened and flavorful, 20 to 30 minutes.

3. TEAR up 1/3 to 1/2 cup of basil leaves (we julienne them) and stir them into the sauce. Cover the pot to keep the sauce warm.

4. PREHEAT the oven to 400°F. Coat a large oven-proof baking dish in a thin layer of olive oil. Spoon a ladle full of sauce into the dish.

5. COOK the gnocchi. Bring a large pot of water to a rolling boil and season with salt. Once boiling, cook the gnocchi according to package instructions.

6. DRAIN the gnocchi and transfer half to the baking dish. Spoon a layer of sauce on top and sprinkle with half of the mozzarella.

7. ADD the remaining gnocchi to the baking dish. Spoon more sauce on top and scatter on the remaining mozzarella. Finish with a layer of sauce and sprinkle with 1/3 cup of grated Parmigiano cheese.

8. BAKE for 5-8 minutes, until the sauce is just bubbly and the cheese is melted. If you want to brown the top, slide the baking dish under the broiler for 1-2 minutes.

9. GARNISH as desired when the dish comes out of the oven, and serve hot. We prefer a little green color, via a few whole basil leaves.

Variations

Add sausage or pancetta in layers in the baking dish.

Add color: a drizzle of pesto sauce on top of the layered dish.

SINGING ABOUT SORRENTO

Perched atop cliffs that separate the town from its busy marinas, Sorrento is a sun-soaked paradise known for dazzling water views and Mount Vesuvius in the distance. No wonder everyone who visits wants to return.

So we couldn’t close without offering you a few of the many variations of the famous song, “Torna a Surriento”:

Andrea Boccelli

Jonas Kaufmann

Mario Lanza

Dean Martin

Luciano Pavarotti

Frank Sinatra

We’ve chosen our favorite artist‡. Who’s yours?

By the way: You may see the song title using “Surriento” instead of Sorrento. That’s because it’s written in the Neapolitan dialect, which differs from standard Italian.

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN PASTA & NOODLES

Pasta and noodles are similar foods with key differences in ingredients, preparation, and cultural origins. While there’s some overlap between the categories (some uncooked varieties Asian wheat noodles can look similar to pasta), they represent distinct culinary traditions with different preparation methods, serving styles, and flavor profiles.

Here are some comparisons of Chinese noodles and pasta:

Mai fun uses thin, round rice noodles that are often labeled as rice vermicelli.

Hor fun rice noodles used for chow fun look similar to fettuccine.

In terms of wheat noodles, those used for lo mein and chow mein look like spaghetti and spaghettini. Udon is thicker Japanese noodle, like spaghettoni. These Asian noodles are made with wheat flour and egg, just like pasta.

However, Chinese noodles are stir-fried, whereas their pasta counterparts are boiled. Japanese udon are boiled.

Another difference is that while pasta is made by rolling and then slicing the dough, Asian wheat noodles are made by pulling and stretching the noodles. As a result they differ in their texture and consistency: springier and bouncier than their pasta counterparts.

More Differences

Origin: Pasta originated in Italy and is associated with Italian cuisine. Noodles originated in China and Found in many Asian cuisines, such as Chinese (lo mein, chow mein), Japanese (ramen, soba, udon), and Thai (pad Thai).

Noodles are believed to have originated in China more than 4,000 years ago.

There are of course European noodles that are non-Italian. We’ll get to them in the next section.

Ingredients: Pasta is made from durum wheat semolina, water, and sometimes eggs and salt. Asian noodles are made from various flours (wheat, rice, buckwheat), or starches (potato, mung bean) and wheat noodles sometimes use salt. Rice and starch noodles do not use it. Ramen use a special alkalin salts (kansui) to increase the pH of dough and makes the noodles firm and chewy texture with a yellowish hue.

Shape: Pasta is made in hundreds of shapes (see some of them here in our Pasta Glossary), Asian noodles are usually long, flat, thin strands or ribbons

Cooking method: Pasta is usually boiled until al dente or baked. Asian noodles used in soup are boiled but other preparations are stir-fried or deep-fried.

What About Pasta Vs. European Noodles?

Etymology: “Pasta” comes directly from the Latin pasta, which means dough or paste, itself derived from the Greek pástē, meaning barley porridge or dough mixed with sauce. In modern Italian, pasta specifically refers to the wheat-based dough.

“Noodle” derives from the German Nudel, a word which first appeared in the 18th century. The existence of of noodles, however, predates then: Noodles first appeared in German cuisine during the Middle Ages, likely around the 13th or 14th century, influenced by Italian pasta, which was introduced through trade routes. The noodles were called by different names in different dialects, for example, Knöpfle, Mus, Teigwaren, and Träsh.

Some examples of non-Italian noodle dishes, all made from wheat flour and sometimes egg, with water or milk:

Finland’s Finska Makaronilåda, macaroni casserole, is made with elbow macaroni, ground meat, eggs, and milk, then baked. A dish from older times is klubbnudlar, Swedish dumpling noodles, which were small boiled wheat noodles or dumpling-like pasta served in soups and stews.

France, through influence of its western border with Germany, serves up buttered noodles (nouilles à l’Alsacienne), noodle soup (soupe aux nouilles), noodles in cream sauce (pâtes d’Alsace) or as a side with with choucroute, and gratin de nouilles, a noodle casserole of egg noodles baked with cheese, cream, and sometimes ham, especially in Alsace.

Germany’s famous noodle dish is Spätzle, as a side, a main dish, or in soups. Eiernudeln is the general term for egg-rich German noodles, often served with gravy-heavy meat dishes. There are also Bandnudeln, wide egg noodles, similar to tagliatelle; Fleckerl, small, square noodles; Hörnchen Nudeln, curved, tubular noodles similar to elbow macaroni; Knöpfle, a smaller and rounder version of Spätzle; Maultaschen, large, square-shaped stuffed noodles similar to ravioli; and Schupfnudeln, thick, long potato-flour noodles, among others. Each has their own traditional preparation. For example, Gaisburger Marsch is a hearty Swabian beef stew with Spätzle or other noodles, potatoes, and beef broth. For dessert there’s Dampfnudeln (sweet noodle dumplings) made from yeasted dough, steamed or baked, and often served with vanilla sauce.

Hungary has nokedli, similar to Spätzle.

Jewish egg noodles (lokshen) are used in both savory and sweet dishes.

Portugal’a cuisine includes noodle soup (sopa de massa), a seafood stew with noodles (massada de peixe), and aletria, a sweet vermicelli pudding.

Russia has lapsha soup noodles, buttered noodles served with meat, and pelmeni (which are technically dumplings like gnocchi). There’s also kotlety s lapshoy, a Soviet-era meal of fried meat patties with buttered egg noodles.

Spain has fideuà, a dish similar to paella but made with short, thin noodles instead of rice, as well as noodle soup and canelones—Catalan cannelloni.

The U.K. makes Victorian noodle soup, Lancashire buttered noodles, and vermicelli pudding.

The U.S. is a happy melting pot of everything.

So, Is It Pasta or Noodles?

A rule of thumb:

If it’s Italian-style, durum wheat-based, and shaped into firm forms, call it pasta.

If it’s soft, egg-heavy, or made from other grains or starches, call it noodles.

When Did “Noodles” & “Macaroni” Become “Pasta” In The U.S.?

In the 18th century and beyond, the term “noodles” appeared with German immigrants, who arrived in the U.S. much earlier than Italians.

The first significant wave of German immigrants arrived in the 18th century, and peaked during 1840s to 1880s.

The wave of Italian immigrants began in the late 1800s, with a peak from the 1880s to the 1920s.

In the early to mid-20th century, “noodles” was a catch-all term for most types of Italian pasta, including macaroni.

Kraft Macaroni & Cheese, introduced in 1937, established the term “macaroni” for elbow macaroni.

While “spaghetti” was a standard in Italian restaurants, those tended to be in cities with big Italian populations. But in the 1920s and 1930s companies like Franco-American began to market canned spaghetti, making the term familiar nationwide.

Everything else was still “noodles.”

|

|

[1] Gnocchi alla Sorrentina. The recipe is below (all photos © DeLallo except as noted).

[2] You can pick up gnocchi just about anywhere. These are potato gnocchi, the most common and traditional type, made with boiled potatoes, flour, and sometimes egg.

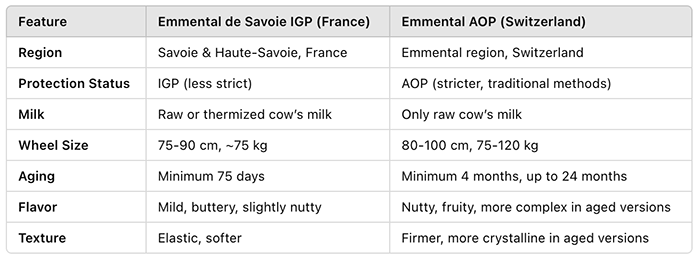

[3] You can also use cheese gnoccchi, made with ricotta cheese instead of potatoes, giving it a lighter texture. You can also find (or make) beets, carrots, pumpkin, and spinach gnocchi, among others (photo by ChatGPT 2025-03-29).

[4] Start with sautéing the garlic in a pan with olive oil.

[5] Add some red pepper flakes for a light layer of flavor (photo © Savory Spice Shop).

[6] Next, open a can of San Marzano tomatoes and pop them into the pan.

[7] Tear up fresh basil leaves and add them to the pan (photo CC0 Public Domain).

[8] Combine the sauce and cooked gnocchi in a baking pan with mozzarella (photo © Svario Photo | Panther Media).

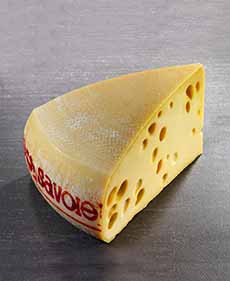

[9] When the dish comes out of the oven, pass the wedge of Parmigiano and the grater so people can add as much (or as little) as they wish (photo © London Deposit | Panther Media).

[10] Sheet Pan Gnocchi With Sausage & Peppers. Here’s the recipe.

[11] Mac & Cheese Gnocchi. Here’s the recipe.

[12] Baked Chicken Parm With Gnocchi. Here’s the recipe.

[13] Gnocchi potato salad—no potatoes, just potato gnocchi. Here’s the recipe.

[14] Italian-Polish fusion: Gnocchi With Kielbasa & Cabbage. Here’s the recipe.

|