|

WE’RE BULLISH ABOUT SHEEP…

…but not just any sheep.

We’re crushing on Sarda sheep, the lovely ovine ladies living the luxe life of Italy’s gemstone island, Sardinia (Sardegna in Italian).

What they produce is the extraordinary milk that makes the extraordinary Pecorino D.O.P (Denominazione d’Origine Protetta, or Protected Designation of Origin) cheese.

D.O.P.* is Italy’s version of France’s Appellation Controlee for wine: It denotes that the product can only be made in certain areas with specific terrain requirements.

The designation is a guarantee of cultural heritage and exceptional quality. You’ll find the best of it under the imprint of 3 Pecorini (#3pecorinicheeses).

A delicious recipe and the history of Pecorino cheese are below.

SARDA SHEEP PRODUCE GREAT MILK & CHEESE

Sarda sheep (photo #4) graze on herbs and shrubs and breathe the clean Mediterranean air of Sardinia’s valleys and mountains.

Their farmers and herders have inherited centuries of ancient techniques that have proved ideal for cheesemaking, resulting in unmistakable flavor (from mellow to tangy) and long-term storage capacity.

Trying to describe the multi-level flavor profile of sheep’s milk cheese depends on the changes that occur as it ages. Always, however, you’ll note an edge and complexity (experts call it “sheepiness”) that non-sheep milk cheeses miss out on.

If you grate heaps of fresh Parmesan onto your pasta, you’ll get fabulous flavor, but you won’t get that fascinating little tipping point gives Pecorino cheese its unique qualities.

Most pecorino cheeses are classified as grana and are granular, hard and sharply flavored.

HOW ENJOY PECORINO CHEESE

Look for Pecorino Sardo marked D.O.P. at a quality cheese store or counter. The label should state how long the cheese has been aged.

Taste-test the different ages of the cheese for comparison. The sharpness depends on the period of maturation, which varies:

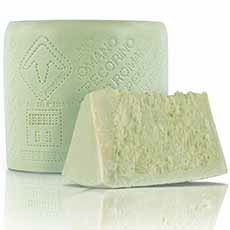

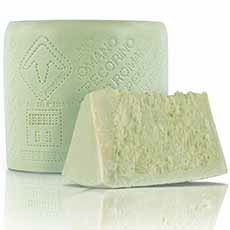

Pecorino Sardo Dolce. The youngest Pecorino is aged for five or 6 months, and it’s called Pecorino Sardo Dolce. Dolce means sweet, referring to the mildness. While it’s very mild, it still has a tiny “sheepy” edge, and is delicious enjoyed on its own on a cheese board along with fruit and/or fruit spreads. Its texture is smooth and velvety (photo #1, photo #5).

Pecorino Romano, aged 6 months or longer, is tangy and wonderful for grating over pasta and salads. You can tell that its flavor is at its peak when it starts to “sweat.” Tiny beads of fatty moisture transport big flavor to recipes, to a cheese board, or for grating. Its surface is craggy, its color starting to yellow (photo #3).

Pecorino Fiore Sardo, or Fiore de Sardegna (“Flower of Sardinia’) is known as “the herders’ and cheesemakers’ cheese. Aged for 8 to 10 months, it is multi-layered: salty and tart, with a depth of flavor inherited from smoking over an open fire made from cork trees, after it has been aged (photo #10 at bottom of article).

There is also a P.D.O. Pecorino Toscano produced in Tuscany, that was not part of this tasting. Here’s more about it.

How We Enjoy It

On a cheese board with figs and pears, honey or jam, even crudités.

Grated or shaved onto salads and soups.

Grated or shaved onto pastas, risotto, grain and potato dishes.

Grated or shaved onto vegetables, especially roasted vegetables

Shaved onto sandwiches.

RECIPE: BAKED ZITI WITH ASPARAGUS AND FIORE SARDO

Fiori Sardo is the finest Pecorino, but substitute Pecorino Romano if you can’t find it.

Prep time is 25 minutes, cook time is 20-25 minutes.

Ingredients For 4 Servings

11 ounces ziti

4 ounces Fiore Sardo D.P.O. cheese

½ pound fresh asparagus, trimmed and tough stems peeled

2 tablespoons olive oil

Half a small onion, finely chopped

3 ounces prosciutto, chopped

3 ounces ricotta cheese

9 ounces bechamel sauce (recipe below)

Salt† and freshly ground pepper to taste

Unsalted butter to taste

Additional Fiore Sardo

________________

†The prosciutto will be salty, so use caution when adding salt to taste.

________________

Preparation

1. PREHEAT the oven to 375°F.

2. PARBOIL the asparagus in a pot of salted water. Test the asparagus for doneness, but do not overcook (it should be slightly firm to the bite). Drain the asparagus, but save the water it was cooked in. Cut the asparagus into bite-size pieces and set aside.

3. HEAT the olive oil in a medium saucepan over medium heat and brown the prosciutto. Add the onion and sauté until translucent, but not browned.

4. ADD a small amount of water to the pan, lower the heat, and cook about 10 minutes. Add the asparagus pieces. Stir and season to taste with salt and pepper.

5. COMBINE the ricotta, bechamel, and the Fiore Sardo in a medium bowl. Stir in the asparagus and prosciutto mixture.

6. COOK the ziti in the reserved asparagus water until al dente. Remove to a large bowl with a slotted spoon and add the ricotta and bechamel mixture. Toss well until all of the ingredients are combined.

7. POUR the mixture into a buttered baking dish, dot the top with butter, and add some additional grated Fiore Sardo. Bake about 20 to 25 minutes, or until mixture is bubbling.

For The Bechamel Sauce

2 tablespoons butter

2 tablespoons flour

1¼ cups milk, hot but not boiling

1/8 teaspoon freshly grated nutmeg to taste

Salt and freshly ground white pepper to taste

Preparation

1. MELT the butter in a small saucepan over medium heat. Whisk in the flour, stirring until you have a smooth white paste.

2. COOK, whisking constantly until mixture is very pale yellow (watch carefully so as not to overcook the flour). Carefully add the hot milk a little at a time, whisking constantly until mixture is smooth and creamy.

3. STIR in the nutmeg, salt, and pepper to taste.

— Rowann Gilman

THE HISTORY OF PECORINO ROMANO CHEESE

Thanks to the Consortium for the Protection of Pecorino Romano Cheese for this history.

Few cheeses in the world have such ancient origins as Pecorino Romano.

For more than 2000 years, the flocks of sheep that graze freely in the countryside of Lazio and Sardinia have produced the milk from which the cheese is made.

A cheese variety of what might be considered the earliest form of today’s Pecorino Romano was first created in the countryside around Rome.

Its method of production being described by Latin authors such as Varro and Pliny the Elder about 2,000 years ago [source].

The ancient Romans were fans of Pecorino Romano. It was prized at banquets in the imperial palaces, and its long-term storage capacity made it a staple food for rations when the Roman legions marched.

Pecorino Romano was so much in use among the Romans that a daily ration of 27 grams was established for the Legionaries, as a supplement to their bread and farro soup.

The cheese was produced in Latium (modern Lazio), the region of central western Italy in which the city of Rome was founded, until 1884.

|

|

] ]

[1] Wheels of Pecorino Sardo and Pecorino Dolce (photos #1 to #7 and 10 © 3 Pecorini | Sopexa).

[2] Fiore Sardo Pecorino, the most aged and treasured by connoisseurs.

[3] Pecorino Romano with its protective wax coating removed.

[4] Fiore Sardo Pecorino, the most aged and treasured by connoisseurs.

[5] A simple cheese board (photo © Lydia Lee).

[6] Serve Pecorino Dolce with beer, cocktails and wine (photo © Lydia Lee).

[7] Pecorino is a favorite with pasta. See the recipe at the left.

[8] Fava Bean, Mint, and Pecorino Romano Bruschetta. Here’s the recipe from Martha Stewart (photo © Martha Stewart).

[9] Skillet-roasted Brussels sprouts with Pecorino. Here’s the recipe from Splendid Table (photo © Splendid Table).

|

Then, due to the city council prohibiting salting the cheese in their shops in Rome, many Roman producers moved to the island of Sardinia, which provided Roman entrepreneurs with a type of soil that was ideal for monoculture farming [source].

Today, the cheese is produced exclusively from the milk of sheep raised on the plains of Lazio and in Sardinia. Most of the cheese is produced on Sardinia.

Per D.O.C. law, Pecorino Romano must be made with lamb rennet from animals raised in the same production area. Thus, is not suitable for vegetarians.

Comments From Homer & Columella

The processing of sheep’s milk was described by Homer (born sometime between the 12th and 8th centuries B.C.E.) It was codified in the following centuries. Columella (4 C.E. to 70 C.E.), a prominent Roman writer on agriculture, gives a detailed description in his “De re rustica”:

“…the milk is generally curdled using lamb’s or kid’s rennet….The milking bucket, when it has been filled with milk, should be kept at a medium heat. Do not let it come near sources of fire…rather keep it well away from fire, and as soon as the liquid is curdled, it should be transferred into baskets or moulds. In fact it is essential that the whey can drain immediately and be separated from the solid matter…. Then when the solid part is removed from the baskets or moulds, it should be placed in a cool, dark place so that it does not go off, on tables as clean as possible, and sprinkled with ground salt so that it can sweat.”

>>> CHEESE GLOSSARY: THE DIFFERENCE TYPES OF CHEESE <<<

>>> THE HISTORY OF CHEESE <<<

________________

*D.O.P., Denominazione d’Origine Protetta is the Italian certification of authenticity of origin. Some other countries in the European Union also use D.O.P. now, including Portugal. See also A.O.C. and D.O.

________________

[10] The three Pecorini from Sardinia: (photo © 3Pecorini).

|

]

]