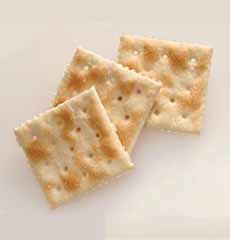

August is National Goat Cheese Month, so this past weekend, we grabbed a log of goat cheese and crackers for our guests. Although a log of fresh goat cheese is spreadable, it’s also crumbly. For the sake of neatness, we decided to pre-spread the crackers.

Then we had a tray full of boring-looking, white-topped crackers. We decided to get to work decorating them with whatever we had at hand.

We thus turned “goat cheese and crackers” into “hors d’oeuvre” to accompany cocktails, wine, and beer.

Whether you decorate the cheese-spread crackers in advance, or create a DIY, garnish-your-own option with ramekins of different toppings, it’s a tasty and fun snack.

Here’s what we had in our kitchen. We went overboard; you can choose just a few of these:

Your favorite crackers

> The history of cheese.

THE HISTORY OF CRACKERS

Crackers are made of flour, water, and salt. Some have other seasonings, but unlike bread, there is no leavening. There are different shapes of crackers—ovals, rings, rounds, squares, and triangles.

And there are many styles, including cheese crackers and rice crackers for snacking; oyster crackers and saltines for soup; biscuits, cream crackers, crispbreads, and others to serve with cheeses and spreads; taralli and other cocktail nibbles; sweeter types like graham crackers; and so on.

In American English, the term “cracker” typically refers to flat biscuits with a savory, salty flavor, as opposed to a cookie, which may be similar in appearance but is made with sugar.

In the U.K., cookies are called biscuits and crackers are either crackers or savory biscuits.

The First Crackers

Long before crackers, the first flatbreads were made from ground grains mixed with water and cooked on hot rocks or griddles over fires. How soft or hard they were cooked, we do not know.

Before “crackers” appeared, there were larger, crispy flatbreads like matzoh, lavash, and other soft flatbreads that were baked to a crispy texture.

Matzoh dates to at least the 13th century B.C.E., when the Israelites fled Egypt with their unleavened bread. We don’t know how crisp it was or was not.

Today’s hard, crisp, thin matzoh seems to have developed sometime in the 17th century, largely because the soft variety, like all fresh bread, would get moldy quickly, and the hard-baked form had a long shelf life [source].

In Medieval times (1100–1200 C.E.) in central and southern Sweden, rye flour was baked into crispbread (knäckebröd, “bread which can be broken”)—also for a long shelf life. The rounds were baked with a hole in the middle so that they could be threaded over a beam and stored suspended from the ceiling. These flatbreads and crispbreads were baked only once or twice a year and kept dry in a storage chamber [source].

For similar reasons, the modern cracker was invented close to the turn of the 19th century, in New England.

A small, crisp bread alternative, the first cracker-like product was made in 1792 by John Pearson of Newburyport, Massachusetts, who mixed flour and water into “pilot bread” [source].

The long shelf life was popular with sailors, who called it hardtack or sea biscuits.

Years later, Pearson sold his business to the company that became Nabisco. Crown Pilot Crackers from Pearson’s recipe were made and sold in New England up until early 2008 (photo #2), and served with traditional chowder recipes.

A big moment in the life of the cracker came in 1801 when another Massachusetts baker, Josiah Bent, burned a batch of biscuits in his brick oven. The crackling noise that emanated from the singed biscuits inspired the name “crackers.”

Bent was a cracker visionary. Beyond selling the dry biscuits to sailors and other travelers, he saw the product’s snack food potential. By 1810, his Boston-area business was booming, and, in later years, Bent sold his enterprise to the National Biscuit Company, which now does business under the Nabisco name.

Soda crackers, later known as Saltines, were described in The Young Housekeeper by William A. Alcott in 1838.

In 1876, F. L. Sommer & Company of St. Joseph, Missouri began to use baking soda (a.k.a. bicarbonate of soda) to leaven its wafer-thin cracker, initially called the Premium Soda Cracker. They were later renamed Saltines because of the baking salt* component.

The formulation quickly became popular and Sommer’s business quadrupled within four years [source].

Cracker trivia: Certain types of crackers contain tiny holes, known in the trade as docking holes (photos #2, #3, and #4). They are punched into the flat dough to stop large air pockets from forming in the cracker while baking.

The Somer company merged with other companies to form American Biscuit Company in 1890. In 1898, after further mergers, American Biscuit Company became part of the National Biscuit Company, which changed its name to Nabisco in 1971.

Nabisco lost its trademark for “Saltine” in 1907 after the term began to be used generically to refer to similar crackers. The word “saltine” appeared in the 1907 Merriam Webster Dictionary defined as “a thin crisp cracker usually sprinkled with salt” [source].

Then, the brand began to call itself Premium crackers. Following a recent redesign, the current boxes are now labeled “The Original Premium Saltine Crackers.”

Over the decades, cracker manufacturers have brought out creativity along with the crunch. Some of America’s favorite crackers (in alphabetical order): Carr’s Table Water Crackers, Cheez-It, Goldfish, Keebler Club Crackers, Mary’s Gone Crackers, Ritz, Toasteds, Town House, and brands we’ve never heard of, like Chicken in a Biskit [source].

________________

*Baking soda, a chemical compound with the formula NaHCO₃, is a salt composed of a sodium cation and a bicarbonate anion.