Fried Egg Breakfast Quesadilla Recipe & Quesadilla History

|

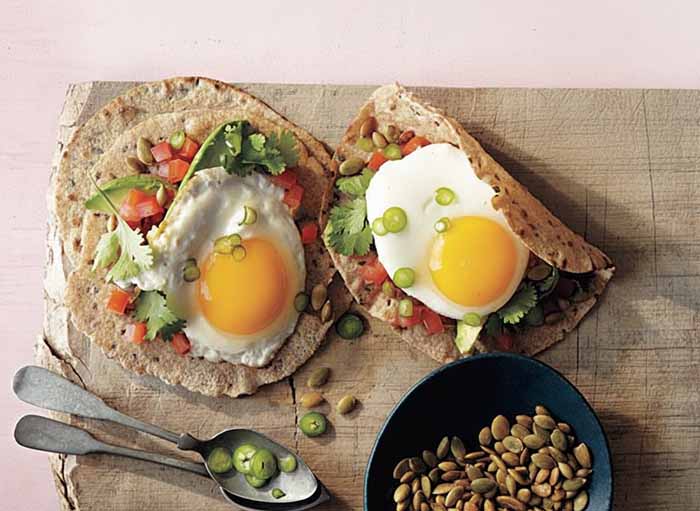

We don’t know what Chef Ingrid Hoffmann is making for Cinco de Mayo, but we’re breakfasting on our adaptation of her Fried Egg Quesadillas (photos #1 and #8). A simple Mexican snack food. A basic Quesadilla is a Mexican snack food: a turnover (photo #1) made with an uncooked tortilla and a variety of fillings—beans, cheese, meats, potatoes, then folded and toasted on a hot griddle (comal) or fried. Regional variations abound. The history of the quesadilla is below. > The year’s 25+ Mexican food holidays. > The year’s 116 breakfast holidays. Ingredients For 2 Servings There are more complex tortilla recipes, including a “sandwich” style with a top and bottom tortilla, cut into wedges (photo #2). It can be served with sides of crema (sour cream), guacamole, or salsa for customization. This recipe (photo #1) is a much quicker version. 1. BRUSH a small nonstick skillet with the oil and heat over medium heat. 2. ADD the eggs one at a time and cook sunny side up for about 2 minutes. Using a spatula, transfer to a plate. While the eggs are cooking… 3. WARM the tortillas in a separate, hot skillet (no oil needed). 4. ASSEMBLE: Spread the warm tortilla with half of the mashed avocado, tomatoes, pine nuts, cilantro, and jalapeño. 5. TOP with an egg, drizzle with extra virgin olive oil, and season with salt and pepper. Fold over and serve. |

[1] Quesadilla, loaded and ready to fold, grab and go (photos #1 and #8 © Chef Ingrid Hoffmann).

|

|

[8] A different view of Chef Ingrid’s fried egg and avocado quesadilla. THE HISTORY OF MEXICAN COOKING & THE QUESADILLA The quesadilla was born in New Spain (what is now Mexico) during colonial times: the period from the arrival of the conquistadors in 1519 to the Mexican War of Independence in 1821, which ended Spanish rule. Dishes included corn pancakes; tamales; tortillas with pounded pastes or wrapped around other foods; all flavored with numerous salsas (sauces), intensely flavored and thickened with seeds and nuts. The Spanish brought with them wheat flour and new types of livestock: cattle, chicken (and their eggs), goat, pigs, sheep. Before then, local animal proteins consisted of fish, quail, turkey, and a small, barkless dog bred for food, the itzcuintli, a [plump] relative of the chihuahua. Cooking oil was scarce until the pigs arrived, yielding lard for frying. Indigenous cooking techniques were limited to baking on a hot griddle, and boiling or steaming in a pot. While olive trees would not grow in New Spain, olive oil arrived by ship from the mother country. |

||

[5] Basic quesadilla: cheese and beans (here’s the recipe from Taste Of Home).

|

The Spanish brought dairying, which produced butter, cheese, and milk. The sugar cane they planted provided sweetness. Barley, rice, and wheat were important new grains. Spices for flavor enhancement included black pepper, cloves, cinnamon, coriander and cilantro (the leaves of the coriander plant), cumin, garlic, oregano, and parsley. Almonds and other sesame seeds augmented native varieties. Produce additions included apples, carrots, cauliflower, lettuce, onions, and oranges. While grapes, like olive trees, would not grow in the climate, imported raisins became an ingredient in the fusion cuisine—i.e., Mexican cooking. (Mind you, the peasant diet was still limited to beans, corn tortillas, and locally gathered foods like avocados.) While the Spanish could not make wine locally, they did teach the Aztecs how to distill agave, into what was called mezcal. The pre-Columbian cultures of Mesoamerica brewed a fermented alcoholic beverage called pulque (think corn-based beer). With the barley they brought, the Spanish brewed their home-style beer. The development of the cuisine was greatly aided by the arrival of Spanish nuns [source]. Experimenting with what was available locally, nuns invented much of the more sophisticated Mexican cuisine, including, but hardly limited to: It’s half indigenous, half Spanish. |

|

|

CHECK OUT WHAT’S HAPPENING ON OUR HOME PAGE, THENIBBLE.COM. |

||