FOOD FUN: Limburger Cheese & Other Washed Rind Cheeses

|

|

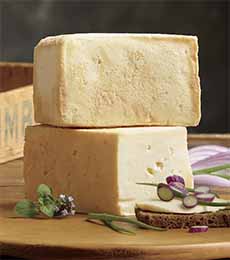

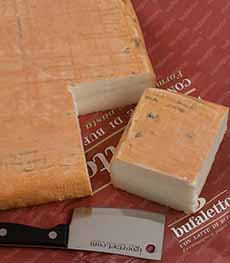

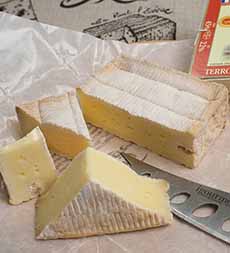

Limburger: It’s a soft cow’s milk cheese, a washed rind cheese with a pungent aroma that has been the butt of jokes for decades. The Wisconsin Cheeseman calls it “Limburger: The Cheese That Nose No Equal.” Infamous for its alleged “stinky feet” aroma, the cheese gets a bad rap. The aroma is more earthy in character. The paste (the cheese under the rind) has a creamy texture and a buttery, mild flavor. Don’t pass buy the opportunity to taste it. In 2019, People Magazine named the Limburger Sandwich at Baumgartner’s Cheese Tavern the best sandwich in Wisconsin [source]. You can make your own version with the ingredients listed below. Full disclosure: We love washed-rind cheeses. Washed rind cheeses are very aromatic. And they’re popular! Beyond the European cheeses from Austria, England, France, Ireland, Italy, Germany, Spain and Switzerland, there are dozens of artisan limburgers made in the U.S. alone. Just search for “washed rind cheese” on the Murray’s Cheese website. Cheese connoisseurs want them. We know that most Americans prefer a more bland type of aroma and taste. Trust us: Limburger’s aroma and flavor pale in comparison to those of truly pungent washed-rind cheeses, like Époisses (ay-PWAZ), from the Burgundy region of France, and Stinky Bishop, made in Gloucestershire, in western England. Whether from Europe or the U.S., we can’t get enough. So here’s an idea: If you think you might love them too, gather three or more types, a lot of good beer, and have a stinky cheese tasting (call it a washed rind cheese tasting if your crowd is more elegant). Use the opportunity to taste different types of beer with them: lager, IPA, porter and stout, for example. If you can find them, include some brett beers and sour beers. Add bread (pumpernickel, raisin, rye—we like them toasted), cured meats, apples and pears, grapes, hazelnuts or marcona almonds, and dried fruits including raisins or sultanas (golden raisins). Add some crisp white wines for the non-beer drinkers, and you’ve got a party! Just don’t party outside in hot weather: The aroma attracts mosquitoes! Note: Don’t worry about white or blue mold on the cheese: It’s often part of longer-aged washed rind cheeses. Sandwich Tip: Limburger sandwiches are the most popular way to eat limburger cheese. Our father’s parents, who came from the “old country,” ate limburger on pumpernickel with raw red onion, often adding lettuce and tomato. Our mother, a foodie, caramelized the onions and used brown mustard mixed with horseradish for her sandwich. But Dad remained old-school, preferring raw red or yellow onions. (He chewed on parsley afterwards.) Known for their powerful aromas, washed rind cheeses are surface-ripened by washing and brushing the cheese throughout the ripening/aging process. These processes cause the cheeses to age more rapidly. They are ripened from the outside in, instead of from the inside out, because the washing liquid helps to break down the proteins and fats inside. Washed rind cheeses also are called red surface bacteria cheeses. Some rinds are indeed reddish or orange, although the colors of a particular cheese can range beyond those, from light pink to brown. Washing is also called brushing and smearing. Different techniques for washing include bathing, where the cheese is dunked into the liquid, or spraying the liquid onto the cheese. The rind color is from the bacteria Brevibacterium linens, abbreviated B. linens, which covers the cheese. But the color also can be enhanced with annatto. But more than the color, B. linens impacts the flavor and acidity of the cheese, and creates a bolder tang and aroma. It’s due to sulfur-containing compounds known as S-methyl thioesters. The washing agent can be beer, brandy, brine, seawater, whey, wine, a mixture of these ingredients, or any other interesting liquid that will impart flavor and create a different chemical balance for the growth of the bacteria. While cheesemaking goes back thousands of years, the oldest-known cheese that is still made today is gorgonzola, in 879 C.E. (here are more oldies). Limburger is a relative newcomer. First made in the early 1800s in the Limburg region of Belgium, by 1830 it was so popular that cheesemakers in the Allgäu region of Germany began making their own. Limburger originated in the Duchy of Limburg, now in the French-speaking Belgian province of Liège. It was first made by Trappist monks near the city of Liège. It no doubt went well with the great Trappist beers they brewed. In Belgium, it is called fromage de Herve cheese, since it originated in the Herve area of the historical Duchy. The cheese became popular and was soon produced across Belgium, Germany, Switzerland and The Netherlands. Like other stinky cheeses (the washed rind cheese group), people either love it or hate it. The longer the cheeses are left to ripen, the stronger the aroma, which is the inspiration behind the phrase, “It is not cheese that smells of feet, it is feet that smell of cheese.” If the cheese has little aroma, it is not ripe. Most of the washed rind cheeses will ripen into soft, pungent cheeses. After 3 months of aging the cheese becomes spreadable. There are a few that ripen into semi-hard cheeses. Today, most of the Europe’s Limburger is made in Germany. Commercial cheese-making in the U.S. began in Green County, Wisconsin around 1840, when Swiss immigrants with cheese-making skills began to arrive in the area. (Today, Wisconsin is the country’s largest-volume cheese-producing state.) Limburger was first produced there in 1867, in the city of Monroe. Cheese maker Rudolph Benkerts, considered Wisconsin’s first cheesemaker, used milk from his flock of cows (here’s more about it). It must have been a crowd pleaser, because a few years later, 25 factories in Green County were producing limburger. By 1930, more than a hundred companies were producing it [source 1, source 2]. In this epicenter of America’s swiss-style cheesemaking, limburger outpaced swiss cheese in annual production by the 1920s. Beyond Wisconsin, the German-speaking populations of Cincinnati and New York, among others, were big limburger consumers. A limburger sandwich with raw onions and mustard was a favorite workingman’s lunch: cheap and washed down with a glass of beer. Apparently it was nearly unthinkable to eat limburger without a beer. The arrival of Prohibition began to curtail production in most American cheese factories [source]. As opposed to the 1920s and 1930s, when the production of limburger exceeded swiss cheese in Wisconsin, thanks to the large German and Swiss populations, Today, the only U.S. limburger producer is the Chalet Cheese Cooperative (in Monroe, Wisconsin). You can buy blocks of limburger cheese, and limburger cheese spread, directly from them. Limburger is also manufactured in Canada by the Oak Grove Cheese Company in New Hamburg, Ontario. *Époisses, a “barnyardy”-smelling cheese style, was developed in the early 16th century by French Cistercian monks at L’Abbaye de Citeaux, outside the village of Époisses in Burgundy. One of the cheese-making monks discovered that brushing the rind of a young cheese with brandy encouraged the growth of orange bacteria (B. linens), which added body and aroma to the cheese. The cheese came to be called Époisses de Bourgogne, Époisses for short. It became very popular, although today, when people are more concerned with odors, it is illegal to carry an Époisses on the public railways. (Similarly, it is illegal to carry an Asian durian fruit on an airline). |

|

|

|

||