The History Of Bananas For National Banana Lovers Day

|

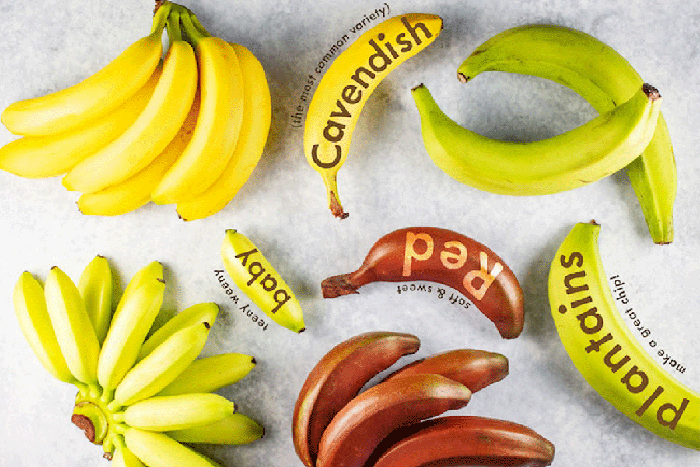

Love bananas? Check out this history of bananas for August 27th, National Banana Lovers Day. But first: While you’re on a long conference call, or waiting for an internet connection that’s taking its time, show your love by decorating a banana (photo #1). > Then enjoy the history of bananas, below. > Also below are America’s favorite banana-based dishes. > Be sure to take a look at this beautiful banana comparison photo, below. > Bananas vs. plantains: the difference. > The year’s 8+ banana holidays. The original, wild, banana was tiny and filled with large seeds the size of peppercorns (photo #2). Bananas were first domesticated in Southeast Asia and Papua New Guinea, by at least 5000 B.C.E. and possibly as far back as 8000 B.C.E. Southeast Asia has the largest diversity of banana species, followed by Africa, indicating a long history of banana cultivation in those regions (source). Over millennia, bananas were bred into the fleshy fruits (botanically, they’re the not fruits but the berries** of herbs) we know today. Many wild banana species can still be found in China, India and Southeast Asia, in the areas south of China, east of India, west of New Guinea and north of Australia. They require a tropical or sub-tropical climate. A 2001 New Yorker article notes: “More than a thousand varieties of banana exist worldwide. The vast majority are not viable for export: Their bunches are too small, their skin is too thin, or their pulp is too bland.” Numerous of these varieties are plantains, are starchy and inedible until cooked (there’s more on plantains below). The article continues: “There are fuzzy bananas whose skins are bubblegum pink; green-and-white striped bananas with pulp the color of orange sherbet; bananas that, when cooked, taste like strawberries (photo #3). “The Double Mahoi plant can produce two bunches at once. The Chinese name of the aromatic Go San Heong banana means “You can smell it from the next mountain.’ The fingers on one banana plant grow fused; another produces bunches of a thousand fingers, each only an inch long.” Alexander the Great introduced bananas to what is now Western Europe in 327 B.C.E. They were brought back from his campaigns in Asia and India, China and Southeast Asia. It took centuries after that—around 800 C.E.—for bananas to make their way to the Middle East. By the 10th century, the banana appears in texts from Palestine and Egypt. From there it diffused into North Africa and Muslim Iberia (southern Spain). During the Medieval Ages, bananas from Granada were considered among the best in the Arab world [source]. Bananas were introduced to the New World in the 16th century via Portuguese sailing ships, which carried them from West Africa to South America. The fruit’s name comes from a West African language [Wolof, the major language in what is now Senegal] where banan means finger. In 1870, a Cape Cod fishing-boat captain named Lorenzo Dow Baker imported 160 bunches of bananas from Jamaica to to Jersey City, New Jersey: the first bananas in the U.S. Shopkeepers hung the bunches and cut off the number of bananas requested by the customer. By 1900 Americans were 15 million bunches of bananas annually; 40 million by 1910. Twenty years later, Baker’s company was renamed United Fruit, today called Chiquita Brands. By the 1960, United Fruit controlled nearly seven hundred million acres of land and 90% of the American banana market. If you’ve had bananas in other countries and find our American imports to be bland in comparison, that’s because the original species Baker imported, the Gros Michel, has long since been replaced by the Cavendish—a blander variety that travels more easily. Many thanks to Wayne Ferrebee for much of this information. Over millennia, farmers hybridized wild species of bananas and selectively bred the different strains into varieties called cultivars. The most delicious exportable cultivar was Gros Michel (Fat Michael, Musa acuminata AAA)—so ideal for farming, transporting and retailing that became more than 80% of bananas cultivated worldwide (here’s more about the variety). A half a century ago, the Gros Michel banana was the principal banana variety imported to the U.S (photo #5, below). They were/are far tastier than the current Cavendish variety: creamier with a tropical fruit taste. The world’s current major banana crop in the world, the Cavendish banana, was grown by a gardener of the William Cavendish, 6th Duke Devonshire, in 1830. He was president of the Royal Horticultural Society. Using a specimen from a lot sent to the Duke by a colleague in Mauritius, the Duke’s head gardener, Joseph Paxton nurtured it and, five years later, the plant flowered and bore fruit. He named the varietal Musa cavendishii, after the family name of the Dukes of Devonshire, Cavendish. He himself became Sir Joseph Paxton for his contribution to England. Cavendish plants were sent with missionaries to Samoa and other South Sea islands, the Pacific and the Canary Islands [source]. When the Gros Michel was wiped out, banana growers turned to the Cavendish. It was a smaller and less tasty fruit, but it was immune to the fungus, able to grow in infected soils, and traveled well. Practically all bananas exported to foreign markets were Cavendish. For decades, practically all bananas exported to foreign markets—China, Europe, North America, etc.—are clones of the first Cavendish plant. Alas, Panama disease has mutated into a new, deadlier strain (Race IV) that not only kills off the Cavendish, but also numerous local breeds of banana around the world. The world is currently in a banana crisis. You can find more information about it online, starting here. Plantains, native to India, are used worldwide in ways similar to potatoes. They are very popular in Western Africa and the Caribbean countries, typically fried or baked. Since popular brands like Dole put their stickers on bananas and plantains alike, here’s how to make sure you’re buying what you want. From Chiquita Brands: |

|

|

|

________________ *Berries do not always refer to the sweet fruit we eat. The broadest meaning is the fruit of a vine. Hawthorne and juniper trees, for example, bear savory berries. Peppercorns are the berries of a vine. There are many inedible berries, such as the red berries of the holly plant. †Alas, fungus persists. Recently these, too, have come under attack by the Race IV fungus, Fusarium oxysporum. ‡The Dwarf Cavendish is so called because the plant itself grows to a shorter height. |

||

[13] Four of the most commercial bananas. Here’s the article from Melissa’s Produce. CHECK OUT WHAT’S HAPPENING ON OUR HOME PAGE, THENIBBLE.COM. |

||