TIP OF THE DAY: Make Your Own Cold Duck Wine Blend

|

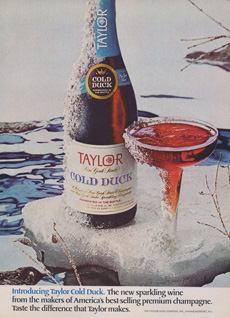

Looking for some summer fun? At the end off a party, instead of opening up new bottles, make a blend of the ends (not dregs*) of existing ones. This idea for party fun (or just-the-two-of-us-at-home fun) was inspired by a memory of college drinking…of a students-and-winos-only sparkling concoction called Cold Duck. What the duck is that? Let’s start with the legend. According to one version of the legend, Prince Clemens Wenceslaus of Saxony (1739 – 1812) mixed Red Burgundy with Champagne, creating a brew he called “kalt ende,” cold end. There are two versions, at least, of this story. Version #1: At the end of a night of banqueting, it seemed like a good idea to not waste the last few ounces of Champagne that remained in opened bottles. Whether from inebriation or economy, he had the Champagne mixed with what was left in bottles of Red Burgundy, and served it to his guests. He called the blend Kalt Ente, Cold End. End of the night? End[s] of the leftovers in the bottles? It doesn’t matter, except that at some point, someone began to bottle combinations of sparkling and still wines. There were white wine versions as well as reds; for example, equal parts Mosel, Rhine wine and Champagne. Version #2 is slightly different: A count (or baron, or perhaps even a prince) returned home for lunch with his hunting party. His butler gave him the bad news that that they had only half as much Champagne needed to serve all of the guests, and half as much Burgundy. The count solved the problem by mixing them together into a “kalte ende,” a mixture of what was left in the cellar. This engendered a German custom to combine the ends of the Champagne with the still wines as the soirée was winding down. Now, fast forward a few centuries. In 1937, Harold Borgman, a German immigrant, restaurateur and owner of Pontchartrain Wine Cellars in Detroit, brought the idea to the U.S. He mixed dry red California burgundy and New York sparkling wine. He properly called it Kalte Ende, Cold End; but someone replaced the “d” with a “t,” creating Cold Duck—which, we might suggest, had more novel marketing appeal. In the 1960s, as more Americans embraced wine*, the blend found its way in inexpensive bottlings from brands like André, Paul Masson and Taylor (photo #2). America’s less sophisticated wine drinkers bought Cold Duck for dinner parties, holiday dinners and general festivities. Most of the grapes used to make Cold Duck were those that would not have held up to a single bottling or blend (i.e., inferior grapes that would have made inferior wines wines). Thus, the wines were chapitalized, which means that sugar was added (this is often done to some good wines in underripe years). In the U.S., Cold Duck spawned Baby Duck, a sweet blend of red and white Chanté wines from Chateauneuf du Pape, a region in the Rhone Valley of France. Baby Duck was the best-selling domestic wine during the 1970s, and “hatched” several imitators: Canada Duck, Cold Turkey, Daddy Duck, Fuddle Duck, Kool Duck and Love-A-Duck. [source]. While the fad passed—especially following national explosion of good California wines in the late 1970s—you can still find André Cold Duck (a brand owned by E & J Gallo Winery). Other brands are sold in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. Serious wine drinkers will duck and run. If you want a sweet, sparkling red, get a good Lambrusco from Italy, rather than a bottle of Cold Duck. As a former wine writer, we still attend the monthly dinners of our wine writers’ group. Everyone brings his/her best bottles to pair with the menu. The finest Bordeaux, Burgundies, and wines from the Rhone and the Loire line the table (we’re a bit Franco-centric, although some dinners are purely American, Australian, Italian, South African, etc.). At the end of the evening, with three inches or so left in each bottle, I often quipped, “If we combined all of these, we’d have one heck of a blend.” |

|

|

|

The dinner hosts never did anything but toss the “cold ends,” until one day I made that blend by pouring all the leftovers into one bottle. I took it home and the next day mixed it with sparkling wine (photo #1), playing with proportions (10% sparkling:90% red, 25%:75%, 50%:50%). The next month, I took home the white wines, and did the same. The results: fun, and imminently drinkable. Plus, telling friends and neighbors that they were drinking a blend of Veuve Clicquot Champagne and Chateau Climens Sauternes was excitement in of itself—not to mention, probably a once-in-a-lifetime experience. You don’t need to have the world’s best wines to do this. We’ve combined the ends of two $15 bottles, a rosé and a Prosecco, and enjoyed them just as much. So don’t dump the “cold ends”: Stick them in the fridge, and when you have enough, blend and drink up! And if this idea appeals to you not, pour the wine into ice cube trays. You can use them for cooking (toss into soups and stews); but we put them into club soda, lemonade, sangria, whatever. ________________ *Following the end of Prohibition in 1933, it was easy to get back into production for beer and spirits: They simply required grain and imported hops. It took seven years or longer to replant and grow wine grape vines to the level where they could make good wine. †Not every bottle, barrel or pot of liquid has “dregs” as the remnants at the bottom. The term refers to something less desirable due to residue: wine with sediment, coffee with grounds or scorched coffee, beer with yeast cells. Unless your bottle is very old, the wines of today are made so that no dregs remain.

|

||