Blood Orange Juice & Gin Cocktail Recipe & The History Of Gin

|

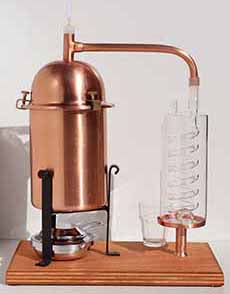

May 4th is National Orange Juice Day, and Mother’s Day is this Sunday. So here’s a cocktail to celebrate both, made with blood orange juice and gin. You can buy and squeeze your own blood orange juice (photo #3), but it’s easy to find it already squeezed in brands like Mongibello and Natalie’s. This cocktail has no fancy name, just a generic one (“Blood Orange Thyme And Gin Cocktail”). So unleash your inner mixologist and name it after yourself, your mother, whoever. The recipe follows, along with: Elsewhere on The Nibble, you’ll find: > The history of blood oranges. January is Ginuary! There’s more exciting gin information below. Thanks to Mongibello, an Italian producer of fresh citrus juices, for this recipe. Ingredients Per Cocktail 1. ADD a handful of ice to a cocktail shaker. Pour in the blood orange juice, gin and simple syrup. 2. SHAKE 4-5 times and strain the drink over fresh ice. 3. TOP with a splash of club soda. Garnish and serve. The distillation of a form of gin can be found as far back as 70 C.E. when a Greek physician named Pedanius Dioscorides published a five-volume encyclopedia on herbal medicine, De materia medica. The encyclopedia detailed the use of juniper berries—gin’s core ingredient—steeped in wine to combat chest ailments. As a medicinal herb, juniper had been an essential part of medical treatments from ancient times to modern herbalists and homeopaths. From the earliest times, alcoholic products were used as medicines. In Baghdad, the first pharmacies were established in 754 [source]. Pharmacists compounded medicines, including those that were alcohol-based. (These old-style pharmacies existed through the early 1900s, when drug companies were able to synthetically reproduce the key properties of the natural substances in tablet form, therefore supplanting most medicines that used alcohol as a base). The basic principles of distillation were known by ancient Greek and Egyptian scholars, including Aristotle. But the roots of modern distillation technology began the alembic still, developed in 800 C.E. by the great Persian alchemist Jabir ibn Hayyan (photo #6). From his discovery, the world began to distill different types of spirits. In the 11th century, in 1055, the Benedictine Monks of Salerno, Italy in their Compendium Solernita, included a recipe for tonic wine infused with juniper berries as well [source]. They distilled it in an alembic still, equipment still used today [source]. Gin as we know it originated in the 16th century when the Dutch began to produce a medicinal spirit called genever (pronounced JEN-ih-ver): a malt wine base and a large amount of juniper berries to mask the harsh flavor. The first known written use of the word “gin” appears in a 1714 book, “The Fable of the Bees, or Private Vices, Publick Benefits,” by one Bernard Mandeville. The British likely began calling genever “gen” for short, which evolved into “gin.” It was a popular drink. But gin was unregulated, and unscrupulous distillers added turpentine, sulphuric acid, and even sawdust into the gin. The result: drinkers suffered insanity and death. The negative results of over-consumption—family breakdown, poverty, and public drunkenness—led to the nickname “Mother’s Ruin.” As a result, a distiller’s license was introduced. It cut back on the bad hooch but was so highly-priced that few people produced gin. Gin was down, but it wasn’t out. It appeared in London during the 1730s, a period known as the Gin Craze, when the city was gripped by an epidemic of public drunkenness. To combat this, the British Parliament passed the Gin Act of 1736, which imposed a massive £50 license fee on anyone selling gin—a price so high (the equivalent of £10,000 today [more than $13,000]) it was effectively a ban on gin. Of course, this simply forced the sale of gin into illicit channels. The first such was the Puss and Mew (photo #8). And 186 years later, the Puss & Mews Distillery began to produce gin in Australia (photo #11). An enterprising man named Captain Dudley Bradstreet found a clever legal loophole. The law required an informer to identify the person selling the gin to make an arrest. Bradstreet realized that if the transaction was anonymous, the authorities couldn’t prosecute. Here’s how his device, known as Puss and Mew (photo #8), worked: |

|

|

[8] A replica of the original Puss and Mew on at the Beefeater Gin Distillery in Kennington, London. An Australian distiller makes a Puss & Mews-brand gin (photo below.) Once Bradstreet’s ruse proved successful, the “Puss and Mew” system was widely adapted by other establishments seeking to bypass the strict Gin Act. A Revolution In Distilling In 1830, a new still was introduced that modified the existing column still and revolutionized the production of all distilled spirits. Gin distillers were able to produce a purer, clear spirit, and the gin phoenix rose from the flames. The British Royal Navy helped to boost gin sales. As sailors traveled to destinations where malaria was prevalent (including India), they brought quinine rations to help prevent and fight the disease. The quinine tasted awful, even with the newly-developed, carbonated Schweppes Indian Tonic Water, launched in 1783. It delivered quinine in a more palatable form, but it still was tough to drink. In the early 1800s, a British officer in colonial India invented the Gin and Tonic when he realized that alcohol helped the tonic water taste better. It could be sherry, gin, rum, locally distilled arrack—whatever was available. Sugar and lime were also added. Over time, gin became the alcohol of preference. You can thank malaria for the appearance of the Gin And Tonic. Gin as a straight spirit, and later in cocktails, became an important part of the modern bar. Today, artisan distillers are producing new styles of gin to offer new aroma and taste experiences to gin fans. While Schweppes Indian Tonic Water was launched in 1783 as an anti-malarial, it was a bitter, unpalatable necessity. But British officers in early-to-mid 1800s in India found a solution: They mixed the bitter quinine with sugar, lime, and water to make it drinkable, adding gin to evolve quinine water from a health necessity into a a palatable, pleasurable drink (the history of the Gin & Tonic). It was an established cocktail in Britain by the late 1800s and a global cocktail sensation by the 1950s. Following the introduction of the Gin and Tonic back in the homeland, gin found its way into the emerging cocktail culture. The late 19th century saw bartenders creating classics like the Martinez (a gin and vermouth precursor to the Martini) and the Tom Collins (sugar syrup and lemon juice). By the early 1900s, the Dry Martini had become the sophisticated drink of choice, cementing gin’s place in cocktail culture. American Prohibition devastated legitimate gin production but sparked illegal manufacturing. A form of bootleg gin, bathtub gin—so called because it was made in a bathtub—was a crude, often dangerous spirit flavored with juniper and other botanicals were steeped in neutral alcohol (often grain alcohol) to mask its harshness, sometimes using a bathtub as a large container for mixing or watering down the hooch. Bootleggers often stole or repurposed industrial alcohol, which was meant for factories, not human consumption. Worse, it was deliberately poisoned at the command of the government so consumers would not drink it. The questionably made liquor flooded speakeasies, where the poor quality of bootleg gin led bartenders to create heavily mixed drinks to mask the harsh flavors, inadvertently advancing cocktail creativity. Post-World War II, gin’s popularity declined dramatically. Vodka, marketed as smooth and modern, became the spirit of choice by the 1960s-70s. Gin became associated with older generations, and many historic gin brands struggled or disappeared. A gin revival began in the late 20th Century. By the 1990s, premium spirits began gaining traction. Bombay Sapphire (launched 1987) helped pioneer the “premium gin” category with its distinctive blue bottle and emphasis on botanical complexity. The 2000s brought an explosion of craft distilling. Small-batch gins with unique botanical profiles proliferated worldwide. Notable developments include: These brands helped transform gin from a declining category into one of the spirits world’s most dynamic and innovative segments: The global gin market more than doubled between 2010 and 2020. Today, gin enjoys unprecedented diversity and popularity, with thousands of craft producers worldwide creating everything from traditional London Dry to experimental, terroir-driven expressions. The world of gin terminology can be a bit confusing because the terms are often used interchangeably in casual conversation by consumers. But they have distinct meanings when you look at production methods and branding. Examples include: Type refers to how the gin is made. This is typically the legal or technical category defined by how the gin is made and what ingredients are used. Examples include: CHECK OUT WHAT’S HAPPENING ON OUR HOME PAGE, THENIBBLE.COM. |

||