Absenthe Brand Absinthe For The Creative People In Your Life

|

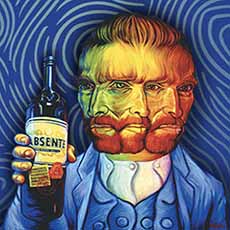

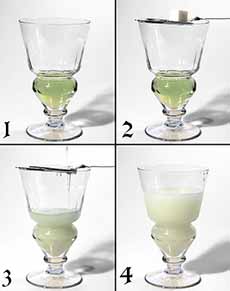

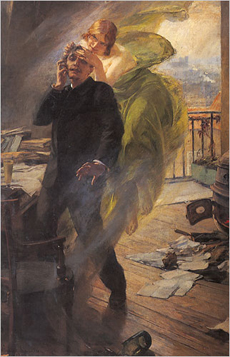

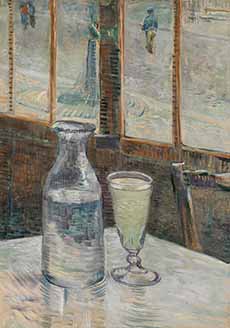

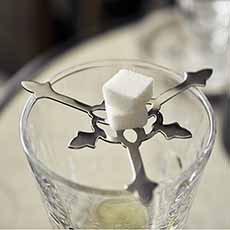

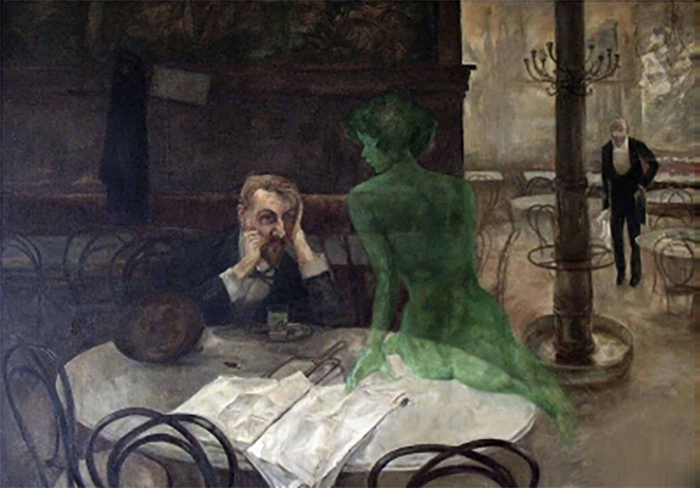

Do you need a special gift for a creative person? How about a bottle of absinthe (photo #1), a green spirit (it’s not a liqueur, as it has no added sugar) that’s distilled from herbs and botanicals? That person should also like licorice. Absinthe is an anise-flavored‡ spirit (check out the difference between anise and licorice in the ‡footnote below). Absinthe is derived from several plants, including the flowers and leaves of Artemisia absinthium*, grand wormwood (also called common wormwood), an herb that contains a controversial chemical compound, thujone. Wormwood has long been demonized for alleged destructive consequences to the mind and body. It was blamed blackouts, pass-outs, hallucinations, and bizarre behavior. (It is a known convulsant when consumed in extremely high doses [source]). It was withdrawn from the market due to the belief that thujone created the psychological and physical health problems associated with it: irresponsible or erratic behavior, withdrawal, dependence, brain damage, and increases in mental illness and suicide [source]. However, contemporary analysis indicates that the chemical thujone in wormwood was present in such minute quantities in properly distilled absinthe as to cause little psychoactive effect. Modern science blames acute alcohol poisoning from drinking twelve to twenty shots a day. Yes, science clued us in, more than 100 years after the ingredient was banned, that the villain was not wormwood but alcoholism. But before science proved the error of thinking, absinthe was banned: in Belgium in 1905, Switzerland in 1908, The Netherlands in 1910, France and the U.S. in 1912 (the U.S. Pure Food Board called it “one of the worst enemies of man, and if we can keep the people of the United States from becoming slaves to this demon, we will do it” [source], in Italy in 1913, in France in 1915, and in Germany in 1923. With time comes progress. In 1988, European Council Directive No. 88/388/EEC allowed certain levels of thujone in foodstuffs. The time was right to lift the ban on absinthe. But you know how slowly bureaucracies move. The ban on absinthe was lifted in the U.S. in 2007, in France not until 2011. This makes a good story to go along with the gift. There are many articles about the ban online. Just print out your favorite and include it with the bottle. There’s actually a National Absinthe Day, celebrated on March 5th to commemorate the day the U.S. lifted the ban. In addition to straight shots, like in the old days, you can find many absinthe cocktail recipes online. For food: While post-ban absinthe contains much less thujone than pre-ban varieties—a fraction of the 100+ mg/l in the days of old—drinkers will not fall into a dreamlike state as did the the drinkers of old (unless they drink way too much and simply fall asleep). There is one exception, made in the Czech Republic at the old strength—and for the highest price (photo #5). In addition to wormwood, absinthe was (and is) also distilled from green anise, sweet fennel, other medicinal and culinary herbs, and other plants, including flowers. > The absinthe ritual (how to drink absinthe—photos #3 and #4). > The Absente brand of absinthe (photos #1 and #2). > Famous absinthe drinkers. Absinthe is classified as a spirit because it is traditionally distilled and bottled without added sugar. With liqueurs, once the base spirit has been distilled, sugar (and other flavorings) is then added according to achieve the desired level of sweetness. There’s no sugar in absinthe. It’s bitter, and that’s why the ritual of drinking it includes dripping water over a sugar cube (see photos #3 and #4). However, because of its bright green color and herbal flavor, people tend to think of absinthe as a liqueur. Even some liquor stores and reputable publications call it a liqueur! But now, you know better. Because of its green tint and the “magical” effect that seemed to inspire creativity, the spirit became nicknamed La Fée Verte (see paintings of The Green Fairy in photos #9 and #22). While absinthe was created for medicinal use in 1792, the earliest recorded use of medical wormwood can be found in the Ebers Papyrus, an Egyptian medical papyrus from 1550 B.C.E. and the most extensive known record of ancient Egyptian medicine [source]. More than three millennia later, the wormwood-based absinthe (named by its inventor after the Greek word for wormwood, apsinthion), was developed by a retired French physician, Dr. Pierre Ordinaire. Originally from the Franche-Comté region of France, Dr. Ordinaire went into self-exile after the French Revolution for political reasons. He settled over the border in the small Swiss town of Couvet, in the Val-de-Travers district of the canton of Neuchâtel. It was there that he created a patent medicine††, the elixir absinthe, in 1782, using local botanicals. Wormwood, a key ingredient, was plentiful in the icy Val-de-Travers region of Switzerland where he lived. The story goes that he traveled the Val de Travers on his horse to sell his absinthe as an all-purpose cure-all for everything from anemia to flatulence. Some customers did say that it cured their ailments [source]. When Dr. Ordinaire died, most stories say, the recipe was bequeathed to his two housekeepers, the Henriod sisters, who produced it from from their home and sold it to pharmacies in the area [source]. On the other hand, one of their ancestors, Kate Henriott-Jauw, author of Alchemy, Alewives, and Alchemy, writes that the sisters had long been creating medicinal tinctures and tisanes for the villagers [source]. The plot thickens here. While some sources say that Dr. Ordinaire supposedly passed his recipe on to the sisters on his deathbed, others suggest that the sisters developed absinthe themselves. If the latter is true, then how did Dr. Ordinaire get involved? One possible explanation: The women were wary of promoting what had become a popular cure-all because of the ever-possible accusation of witchcraft, a criminal offense that was still used in the 20th century to prosecute spiritualists and Gypsies. It wasn’t repealed until 1951. So in this alternate scenario, they approached the good doctor. “His charming nature, good looks, and respectable title of Doctor were well embraced and he proved to be a most natural salesman,” notes Ms. Henriott-Jauw. In fact: “His credibility and successful promotions led to the purchasing of said recipe by a French businessman, Major Dubied.” The truth is out there, Special Agent Fox Mulder reminds us. And Dr. Ordinaire remains credited with being the first to sell absinthe. In 1797, the Henriod sisters sold their recipe to a Frenchman, Major Daniel-Henri Dubied, born in Couvet to a family of lace merchants. That same year, his daughter Emilie married Henri-Louis Perrenoud (he later changed the spelling to Pernod) son of a local distiller, Abraham-Louis Perrenoud. In 1798 the Major, his sons Marcellin and Constant, and his new son-in-law Henri-Louis Pernod, opened the first commercial absinthe distillery, in Couvet: Dubied Père et Fils. The mission was production of absinthe as a recreational alcohol. Some sources say that Abraham-Louis Perrenoud established the first commercial absinthe distillery in 1794 to produce an alcoholic beverage, as opposed to a medicinal cure [source]. But whoever was first, the medical elixir became a popular recreational drink: People loved the taste and the effect. Pernod had learned distillation from his father. He took over Dubied Père et Fils and built a larger distillery in Pontarlier, France, just across the Swiss border. Moving enabled the distiller to avoid the high tariffs placed on liquor imported into France. At this time, Henri-Louis changed the spelling of his surname to Pernod and renamed the company Pernod Fils. Due to his choice of location, the small community of Pontarlier eventually became the world center of absinthe production, home to 28 commercial absinthe distilleries [source]. Mass production in Pontarlier enabled the price of absinthe to drop significantly and the market expanded [source]. In 1827, Pernod’s son J. Édouard took the reins the company and increased distribution, significantly to North and South America. After absinthe was banned in France in 1915, Pernod pivoted to create an anise-flavored liqueur called Pernod Anise. It had a similar licorice-like flavor profile as absinthe but was wormwood free. In 1932 Paul Ricard, a young man from Marseille who worked in his family’s wine business, learned about pastis, a regional anise-flavored herbal liqueur. He made his own version from an old family recipe, using ingredients like star anise, fennel, licorice, and other aromatic plants. He invented the brand name Pastis‡‡‡‡, and it quickly became the market leader in anise/licorice-flavored drinks, overtaking other brands including Pernod Anise. Pastis is usually served diluted with water, which makes it cloudy. Sound familiar? Today the company is called Pernod Ricard, known for its anise liqueur, Pastis. After the thujone ban was lifted, it returned to producing absinthe as well. In 2001, Pernod Ricard released an absinthe claimed to be “inspired by the old formula.” The Pernod and Ricard companies merged in 1975, creating Pernod Ricard. Today it’s the second-largest distiller in the world, behind Diageo. Back to the 19th century… The green spirit rapidly traveled from the south of France to the café tables of Montmartre in Paris. Dr. Ordinaire’s tasty tipple quenched the throats of artists, musicians, writers and poets alike, becoming the drink of choice for the bohemians‡‡‡ of Paris during La Belle Époque‡‡. From there, absinthe became ubiquitous in bars, cafés, and cabarets, popular among all social classes. It became common practice for a wide array of people to enjoy a glass of the now-trending and affordable Absinthe Ordinaire after work. This gave rise to “L’Heure Verte” (The Green Hour) at 5 p.m. (that’s 17 hours on Europe’s 24-hour notation, called military time in the U.S.). Drinkers of all sorts headed to a café for a glass. Like today, cafés were the place to socialize, and cafés were filled with drinkers and their glasses of the verdant liquor. During the Franco-Algerian War (1830-1847), French soldiers were given absinthe to prevent fevers, malaria, and dysentery (wormwood is believed to act as a mild antiparasitic). When the war ended, the soldiers returned to France with a taste for absinthe. The spirit’s popularity was even more enhanced by the unfortunate results of the phylloxera plagues of the 1860s and 1880s. These tiny insect pests attack grapevines worldwide, feeding on the roots and killing the vines. They decimated European vineyards, creating massive wine shortages across most of the grape-growing regions on the Continent—not just France, but Germany, Hungary, Italy, Portugal, and Spain. In the absence of wine, absinthe became France’s most fashionable drink—the “national drink” of the late 19th century. Less expensive than wine, it was affordable enough to be the tipple of choice among the poor as well. Absinthe crossed the pond to the U.S. It was consumed in most large cities in the U.S., but New Orleans became its American center because of the large French population of French. So much absinthe was consumed in New Orleans that Europeans nicknamed the city “the little Paris of North America.” The Old Absinthe House, on Bourbon Street was the city’s most popular meeting place for absintheurs, including such luminaries as Ernest Hemingway, Mark Twain, and Oscar Wilde [source]. It’s still open. Stop in for an Absinthe Frappe. Trivia: The modern American “Happy Hour,” where alcohol was consumed (earlier “happy hours” were not alcoholic events), didn’t begin until Prohibition (the history of Happy Hour). Absinthe was most popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, especially in France, where 1890s were known as the Absinthe Decade. During its peak in 1910, the French consumed a staggering 36 million liters of absinthe per year. By 1913, the French were consuming 60 liters of absinthe per person [source]. But unscrupulous producers of poor quality, and sometimes even toxic, absinthe, together with the demon thujone and a highly publicized Swiss murder case, turned public opinion against absinthe. That, along with the growing temperance movement, led to its downfall. In France, people traditionally diluted absinthe with cold water and sugar to make to make the bitterness of the wormwood more palatable. They still do. This is known as the “absinthe ritual.” Water is slowly dripped over a sugar cube on a small silver slotted spoon. It creates a cloudy mixture called a “louche,” which refers to the milky, cloudy appearance that absinthe takes on when water is added to it. First, the intense bitterness of wormwood and other herbs† made it sought after as an aperitif, meant to stimulate digestion before a meal. (Campari, Cynar, and Fernet-Branca, brands widely sold today, are made for the same reason.) Before modern medicine, when science did not understand how to solve many medical issues and often made things worse (e.g. bloodletting). Digestive issues from stomach aches to constipation were rampant, especially among the affluent, who ate rich diets with minimal fiber. Second, the drinking experience is as much about the preparation ritual as the flavor. The ritualistic preparation is part of its attraction. The cloudy transformation in color and texture created by the sugar and water (called the “louche”) has an appealing visual effect. The water is needed because of the high alcohol content, which makes it difficult for sugar will to dissolve simply by tossing into the glass. These were the days before granulated sugar. Sugar was processed from cane juice and molded into tall cones. People needed to shave off the amount of sugar they needed (the history of sugar). Fortunally for absinthe drinkers, sugar cubes were created in 1841 by Jakub Kryštof Rad (in what is now the Czech Republic). Absente is made with a nine herbs and botanicals, including green anise, lemon balm, peppermint, star anise, and wormwood. The brand uses southern wormwood (southernwood, Artemisia abrotanum) and which is less bitter than grand/common wormwood, Artemisia absinthium, the traditional species. Produced in the South of France, Absente follows one of the oldest-known absinthe recipes, using the finest artisanal distillation method. Distilled to 110 proof (55% A.B.V.), Absente 110 is an overproof**** spirit, the same absinthe proof drunk by poets and artists 150 years ago. You can find it for $60 a bottle. It has an intense, light, fresh, floral aromas, and a well-balanced, complex palate with subtle flavors of anise/licorice, peppermint, and spice. The finish is spicy and bitter. According to an account on the BBC website, it’s hard to overstate the cultural impact of absinthe. From 1859, when Édouard Manet’s painting “The Absinthe Drinker” (photo #7) shocked the annual Salon de Paris, to 1914, when Pablo Picasso created his painted bronze sculpture, The Glass of Absinthe (photo #16), absinthe was a character in art as well as a presence in the glass. During La Belle Époque‡‡, The Green Fairy—nicknamed after its vibrant color—was the drink of choice for so many writers and artists in Paris that five o’clock was known as L’Heure Verte. The Green Hour was perhaps the original happy hour when cafes filled with drinkers sitting with glasses of the verdant liquor. An overload of absinthe created an assortment of visions, hallucinations dream-like states that filtered into the artistic work of artists. According to the BBC, absinthe shaped Symbolism, Surrealism, Modernism, Impressionism, Post-Impressionism and Cubism. Dozens of artists painted absinthe drinkers and the ritual paraphernalia: a glass, slotted spoon, sugar cubes, and fountains dripping cold water to dilute the spirit [source]. Here are some of the prominent artists and writers who were captivated by The Green Fairy. |

|

|

|

It can’t be scientifically measured, but we do love this anecdote about Toulouse-Lautrec: “Toulouse-Lautrec’s pictures were described by Gustave Moreau as ‘painted entirely in absinthe’; he would stop at every bar in Montmartre in order to étouffer un perroquet (choke a parrot), in the slang of the period; and he had a specially made hollow walking-stick which held an emergency half-litre stash of absinthe and a tiny shot glass.” [source] In defense of Oscar Wilde: Please note that the dramatist is often mentioned as one of the great absinthe drinkers. However, there are no direct sources to confirm this. No references to absinthe can be found in any of Wilde’s works or letters. Today’s Absinthe Celebrity: The goth rocker Marilyn Manson, known for drinking absinthe, launched his own brand, Mansinthe, in 2007 (photo #6). It’s an overproof, made in Switzerland at 133 proof, 66.5% A.B.V. Yes, you can buy it. In 1859, Édouard Manet submitted his painting, The Absinthe Drinker (photo #7), to the annual Salon de Paris. One of the earliest-known depictions of absinthe in art, it a shocked the art world and was rejected by the Salon. Only one of some 50 members, Eugène Delacrox, voted for its inclusion. Why the rejection? The main objections were the topic and size. Absinthe art continued; some of our favorite examples appear in photos #7 through #16 at the right, plus #22 below. In 1914, Pablo Picasso created a bronze sculpture, The Glass of Absinthe, which he then painted [photo #16].

CHECK OUT WHAT’S HAPPENING ON OUR HOME PAGE, THENIBBLE.COM. Sage and sage oil, from a completely different botanical family (Lamiaceae, genus Salvia, species officinalis), contain thujone. To make sage tea, you can use 1 tablespoon (15 grams) of fresh sage leaves in a cup of water. The EU has limited the amount of thujone from sage a food product may contain to 25mg/kg. That would equal 50g sage leaves in 1 kg prepared food [source0. Tarragon contains a very small amount of thujone, considered negligible and not a cause for concern in culinary quantities. Other, less common herbs also contain thujone. **The term muse comes from the Greek word mousai, which refers to the nine goddesses of the arts and sciences in Greek mythology. ***The cloudiness occurs because the components with poor water solubility—especially anise, fennel, and star anise—drop out of solution and cloud the drink. The preparation typically contains 1 part absinthe to 3–5 parts water. Note that “louche” (pronounced loosh) has other meanings. The word derives from the Latin luscus, meaning blind in one eye or having poor sight. The first meaning of the French louche, is squinting or cross-eyed. From this evolved the adjective louche, meaning decadent, dubious, fishy, shady, or sinister. For some reason we could not uncover, “la louche” is the word for a ladle. ****An overproof spirit contains more than 50% alcohol by volume (A.B.V.), which is higher than the standard 40% A.B.V. for most spirits sold in the U.S. Overproof spirits are also known as barrel strength or cask strength. †Other edible members of the Asteraceae family (commonly known as the chrysanthemum family) include artichoke, burdock, chicory, chamomile, chrysanthemum, dandelion, endive, ironweed, lettuce, salsify, and sunflower. Chamomile, chrysanthemum, and ironweed are used to brew homeopathic teas. ††A patent medicine is a non-prescription medicine that is sold directly to consumers as a cure-all for a variety of ailments. Other examples of patent medicines that became popular drinks and still exist today: ‡The difference between anise and licorice: The two share a similar flavor and aroma, but they are unrelated plants from different botanical families. different plants with distinct origins. Anise, Pimpinella anisum, belongs to the carrot family Apiaceae, while licorice belongs to the pea family, Fabaceae. Both anise and licorice have a sweet, slightly spicy, and aromatic flavor often described as licorice-like due to the presence of anethole, a bioactive compound and flavoring agent found in the essential oils of many plants. Both anise and licorice contain it, along with basil, caraway, chervil, fennel, star anise, tarragon, and others. The next time you taste any of these latter herbs and spices, look for the anise/licorice flavor. Another key difference between anise and licorice: Anise is the seed of the flowering anise plant, while licorice flavoring is obtained from the root of the licorice plant. ‡‡La Belle Époque (The Pretty Era) was a worldwide phenomenon. In Paris took place from 1871 to 1914, from the end of the Franco-Prussian War to the outbreak of World War I. It is regarded as Europe’s Golden Age. Paris saw the construction of the Eiffel Tower, the Paris Metro, and the completion of the Paris Opera. Great artists like Toulouse-Lautrec and Renoir. In less than fifty years, Europe witnessed vast developments on the political, socio-economic, cultural, and technological fronts. This transformative era received its name, La Belle Époque, in retrospect from a person whose name is lost to history. The retrospective looked at the era of peace and prosperity following the horrors of the Franco-Prussian War, innocent of the oncoming of the even more horrible World War I. Prominent artists of this post-Impressionist time include Jean Béraud, Émile Bernard, Giovanni Boldini, Pierre Bonnard, Maurice Denis, Paul César Helleu, Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse, Gustave Moreau, Alphonse Mucha, Odilon Redon, Auguste Rodin, Henri Rousseau, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and Édouard Vuillard. Notable writers were Paul Bourget, Colette, Alain-Fournier, Anatole France, André Gide, Joris-Karl Huysmans, Alfred Jarry, Jean Jaurès, Stéphane Mallarmé, Guy de Maupassant, Charles Péguy, Marcel Proust, and Émile Zola. While not French, we must add to this list the German Thomas Mann. Poets and playrights: Guillaume Apollinaire, Charles Baudelaire, Georges Feydeau, Arthur Rimbaud, and Paul Verlaine. Musicians: Emmerich Kálmán, Franz Lehár, Johann Strauss III, Francesco Paolo Tosti and classical musicians Lili Boulanger, Claude Debussy, Frederick Delius, Gabriel Fauré, César Franck, Edvard Grieg, Jules Massenet, Maurice Ravel, Camille Saint-Saëns, Erik Satie, and Igor Stravinsky. Dance: Loie Fuller, Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes with Vaslav Nijinsky. ‡‡‡The Bohemians of Paris were a group of young artists, writers, musicians, actors, and intellectuals who lived in Paris in the 19th century, many in Montmartre, near the Moulin Rouge. The term “Bohemian” was first used in Paris judgmentally, to describe Roma people (p.k.a. gypsies), vilified outsiders from conventional society, who many thought came from Bohemia, a part of the Austro-Hungarian region (now in the Czech Republic). This was a misconception. The Roma people did not originate in Bohemia. They are believed to have come from the Indian subcontinent, migrating westward through Europe over time. The artistic types of Montmarte, similarly perceived as outsiders from conventional society, were also given equally judgementally to them. The name became romanticized by the artists. ‡‡‡‡Ricard named drink Pastis from a portmanteau of the Provençal “pastisson” and Italian “pasticcio,” both meaning “mixture” [source]. |

||