A New Pizza Holiday: National Tavern-Style Pizza Day

|

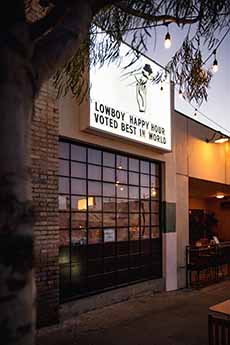

Tavern-style pizza was created in Chicago as a free bar snack (see tavern-style’s history below). While the city may be known for its hearty deep dish pizza*, the thin crust, tavern-style pie is what Chicagoans turn to most often. Tavern-style pizza is a round pie with a very thin crust. The crust is slimmer, lighter, and crisper than the basic pizza crust. For reasons you’ll see shortly, the pie is cut into small squares rather than the conventional pie-slice triangles (photo #1). From a self-service tray at the bar, no plates were needed. The pie was cut into small squares that fit neatly on a paper napkin. Square slices were smaller than pie-shaped slices, creating more servings per pie. Tavern-style may be less well-known in other areas of the country, but it has long been a beloved favorite of Chicago’s cuisine. > The 40+ different types of pizza. > The history of tavern-style pizza follows below. > The history of bar food is also below. > A year of pizza holidays. Tavern-style pizza originated in Chicago’s taverns in the 1930s as a way to encourage customers to stay and drink more. The square shape of the slices allowed taverns to serve pizza without plates, serving them on a napkin. While the style was popularized by local taverns and bars, the originator of the round pie with square slices seems to be lost to history. Pizza as a culinary staple did not catch on in Chicago until the post-Prohibition 1940s. Local taverns served the pizza as a free accompaniment to alcohol, to enticed patrons to stay longer and drink more. The square-shape slice pie is also known as the “party cut” because it’s easy to share at kids’ birthday parties (where “tavern” food would be out of place). You can get tavern-style pizza in any Chicago neighborhood. Even Pizza Hut sells them. > The difference between a bar and a tavern. Food and drink have been sold together since the first refreshment stands for travelers appeared in the ancient world. As taverns evolved and locals as well as those passing through desired food with their drinks, different cultures developed their own concept of bar food: a British pub fare, Japanese izakaya snacks, and Spanish tapas, for example. The 19th century tavern owners in the United States introduced free snacks like peanuts, pretzels, and pickles, to those who purchased a drink. It was a win-win: The saltiness encouraged more drinking (higher alcohol sales), and if they filled up on snacks, the customers didn’t have to spending money on dinner. More elaborate free food tended to be a city-specific promotion. When one saloon owner started the promotion, others had to jump in. Boston. In the late 1800s, some Boston saloons eateries charged 5 cents for a schooner of beer, which included free cheese and crackers or even sandwich—see photo #6 [source]. New Orleans. In 1875, The New York Times wrote of elaborate free lunches as a “custom peculiar to the Crescent City.” [New Orleans]: “In every one of the drinking saloons which fill the city a meal of some sort is served free every day.” Any drink could be had for 15¢. At one place, the repast included bread and butter, oyster soup, roast beef, potatoes, stewed mutton, stewed tomatoes, and macaroni à la Français (mac and cheese with a white sauce). The proprietor noted that the patrons included “at least a dozen old fellows who come here every day, take one fifteen cent drink, eat a dinner which would have cost them $1 in a restaurant, and then complain that the beef is tough or the potatoes watery source].” (Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.‡) New York City. Through the 19th century, New York City saloons on nearly every street corner attracted customers with an offer of free lunch with the purchase of beer or whiskey (source). Caviar lovers: Would you believe that during the 19th and early 20th centuries, when wild sturgeon numbers were flourishing in American rivers, caviar was often given away at bars beginning with New York City’s steady supply from the Hudson River? The salty taste engendered thirst, just like the salty snacks. But there was a downside—see the †footnote [source]. Milwaukee. From the late 19th century until Prohibition closed the taverns in 1920, Milwaukee saloons were well known for providing large spreads of free food for their customers. The higher-class taverns and hotel bars downtown served free hot lunches of sandwiches, ham, beef, and sausages with their 5-cent beers. These were extremely popular among businessmen and clerks. From the Milwaukee Journal: The Milwaukee Journal noted that “A man needed a drink at lunch to ease the pressure of the work-day and a healthy snack of sausage would make that glass of beer so much better. Extra salty ham or pretzels would require an extra beer or two to help wash it down. Prohibition (1920-1933) shut down the bars, but speakeasies often served small plates or snacks. Post-Prohibition. Bars began to expand their offerings of free snacks. Chips, popcorn, olives, and even cubes of cheese and slices of salami were added to the freebie offerings, with the goal of extending the time customers spent at the bar. Then came Happy Hour. The concept emerged in the 1980s, to attract customers during slower times (e.g. 4 p.m. to 6 p.m.). Often-discounted drinks—beer, wine, and cocktails—were just half of the happiness. The most sought-after Happy Hour bars also offered quite a spread. Beyond the salty snacks, there were trays of crudités and chafing dishes of finger foods: pigs in blankets, Chinese dumplings and mini egg rolls, mini kabobs, meatballs, nachos, sliders, wings, and small plates tapas-style dishes (photo #7). For the price of a drink, a customer could pull together a free dinner from the fixings. It was a revolution in after-work drinking. Singles who might have left work and gone home met with friends and colleagues. The atmosphere was buzzing. Some became hot spots (photo #8). The popularity of Happy Hour foods led to an explosion of casual bar food menus. For bars that didn’t care to give food away, bar food created a new profit center. It also enticed new customers who wanted a quick dinner and would have gone to a diner or other casual spot. Bar food menus evolved to the gastro pubs that blossomed in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, offering drinks with higher-quality food, and wine bars with gourmet cheeses, charcuterie, and other fine fare. A bar and a tavern both serve alcohol, but they have distinct historical and functional differences. In modern usage, the terms are often interchangeable, but bars emphasize drinking, while taverns have a more food-and-community-centered atmosphere [source: Chat GPT]. Bar |

|

|

|

Home Run Inn, today a producer of frozen tavern-style pizza, is a family-owned business. It has roots as a cozy little tavern founded on Chicago’s South Side in 1923. The signature crispy crust tavern-style pizza has been served there since the early 1940s. Co-founder Mary Grittani and her son-in-law, Nick Perrino, had the idea to place complimentary thin-crust pizza, cut into squares, at the bar counter as a snack to go with the drinks. The family’s original recipe from Bari, Italy—a hand-pinched crispy crust, zesty sauce and plentiful cheese—soon became a hit. They then began selling the pizza. In 1947 a baseball hit from a nearby park crashed through the window of the tavern, resulting in a name change from Nicola’s Tavern to Home Run Inn. The company was among the pioneers in the frozen pizza category. A regular customer from Wisconsin frequently requested his take-out pizza to be partially baked. This piqued the curiosity of co-founder Vincent Grittani. He discovered that the customer would put the pizza in his icebox and finish baking it later, at home. Home Run Inn tavern-style frozen pizzas launched in the 1960s. The brand is now one of the top 10 pizza brands, sold in grocery stores nationwide. The business is now run by the fourth generation. In addition to the frozen pizza business, there are nine Home Run Inn dine-in pizzerias in the greater Chicago area. *The crust of Chicago deep-dish pizza is thick and buttery. It is often described as having a flaky, pie-like crust texture. It’s typically made with a higher fat content, using ingredients like butter or oil in the dough (there’s no fat in a conventional pizza crust). The crust is pressed into a deep, round pan, creating a sturdy base that can hold several inches worth of tomato sauce, cheese, and toppings—a hearty, filling pizza. The typical pizza crust is made with all-purpose or bread flour, water, yeast, and salt. Some recipes add a bit of sugar to help feed the yeast and enhance browning. Many pizza dough recipes also include olive oil to enhance the texture and flavor. Oil helps make the dough easier to stretch, provides a slight crispness when baked, and can prevent the crust from becoming too tough or dry. †Before long, a thriving industry developed around America’s wild sturgeon, which thrived in rivers from coast to coast. The U.S. became the largest caviar exporter in the world. This, in turn, led to over-fishing, which coupled with pollution and river damming, caused a precipitous decline in native sturgeon populations, bringing them to the brink of extinction (source). CHECK OUT WHAT’S HAPPENING ON OUR HOME PAGE, THENIBBLE.COM. |

||