|

[1] Baking soda made it so much easier for breads and cakes to rise (Gemini Photo).

[2] The base material, a natural mineral called nahcolite that’s refined into baking soda (photo Rob Lavinsky | CC-BY-SA-3.0º.

[3] The world’s most recognized baking soda (photo © Church & Dwight).

[4] 1950s Arm & Hammer Baking Soda ad. It’s available for sale on Ebay.

Popular Uses In The Kitchen

[5] Bread rises thanks to baking soda (photo © Good Eggs).

[6] Cake and cupcakes rise with baking soda (photo © Tommy Bahama).

[7] Cookies spread in the oven and are chewy when they cool, thanks to baking soda (photo © Bella Baker).

[8] Pancakes rise and are fluffy (photo © D.K. Gilbey | Dreamstime).

[9] Soft pretzels need leavening. Otherwise, you get rock-hard pretzels (photo © King Arthur Baking).

[10] Biscuits too, if you want them to be tender like these buttermilk biscuits†† (photo © Robyn Mac | Fotolia).

[11] Tip: Add a pinch of baking soda to an omelet to make it fluffier (photo © Peach Valley Cafe).

|

|

National Bicarbonate of Soda Day, December 30th, celebrates the versatile household staple also known as baking soda, bread soda, cooking soda, or sodium bicarbonate. There’s also saleratus, but more about that later.

Its use in the kitchen is in baking as leavener* (to make dough rise), and in cleaning.

It’s mildly acidic when mixed with water, so dirt and grease dissolve more efficiently.

It’s a natural deodorizer, for fridge and garbage can.

As a gentle abrasive, it’s a handy cleaner for kitchen appliances, pots, and pans.

And when you overindulge and find yourself with heartburn or indigestion, it’s an FDA-approved antacid. (Alka-Seltzer contains sodium bicarbonate, along with citric acid and aspirin.)

Baking soda has other home uses, from personal care (deodorants, scrubs, shampoos, toothpaste, and much more).

Not to mention a favorite kids’ science project, the erupting volcano.

It has numerous industrial uses as well: agriculture, animal feed, fire extinguishers, metallurgy, plastics, textile dyeing, and water treatment, among others.

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN BAKING SODA & BAKING POWDER

Both substances are sodium bicarbonate. However:

Baking powder includes acid and only needs liquid to activate it. Cream of Tartar (potassium bitartrate, the potassium acid salt of tartaric acid) is the most common dry acid in commercial baking powder. Since baking powder brings its own acid, it only needs liquid and heat to work, making it suitable for recipes without other acidic components (buttermik, yogurt, etc.) When baking soda (a base) meets an acid and moisture, they neutralize each other, producing carbon dioxide (CO2) bubbles, which makes the dough rise.

Baking soda does not include an acid and requires both acid and liquid to activate and create bubbles for rising. These can be vinegar (acetic acid), lemon juice (citric acid), dairy with lactic acid (buttermilk, sour cream, yogurt), or other naturally acidic ingredients (cocoa powder, honey, molasses, other citrus juices).

> The difference between baking soda and baking powder.

> Baking powder: How it’s different, how to use it, who invented it.

Below:

> The history of baking soda.

> The history of leavening.

THE HISTORY OF BAKING SODA

Ancient societies discovered natron, a naturally occurring mineral deposit primarily composed of sodium carbonate and some sodium bicarbonate. It was mined from dry lake beds.

Ancient Egypt: Natron was used by the Egyptians to dry out bodies during the embalming and mummification process. For the living, it was also used as an early mouthwash, as soap-like cleaning agent, and for making glass.

The ability to produce pure sodium bicarbonate in a lab came much later, with the advancement of chemistry and the need for a reliable source of alkali for industrial use.

Europe, 18th/19th centuries: Scientists discovered how to turn the natron into sodium bicarbonate. First, in 1791, French chemist Nicolas Leblanc developed a process to produce soda ash (sodium carbonate), the precursor to baking soda. In 1801, German pharmacist Valentin Rose the Younger built on that to discover sodium bicarbonate.

The invention of baking powder: In the 1840s and 50s, chemists like Alfred Bird and Eben Norton Horsford realized they could package baking soda with a dry acid (like cream of tartar). This created baking powder, which only needed water to react, making baking much more accessible to the average person.

United States, 19th century: In 1834, Austin Church, a physician, began to experiment with sodium carbonate and carbon dioxide to try to find a yeast substitute for making bread rise. He found that bicarbonate of soda was superior to the potash then used for baking. Church gave up his medical practice and established a factory (his farmhouse kitchen) to make pearlash and saleratus in Rochester, New York.

In 1846, baking soda as a commercial product for the home took off in a big way when Church enlisted his brother-in-law, John Dwight, to undertake sales and distribution. They refined and packaged the product in Dwight’s kitchen, in one-pound colorful paper bags for grocers’ shelves. They operated separate but related companies.

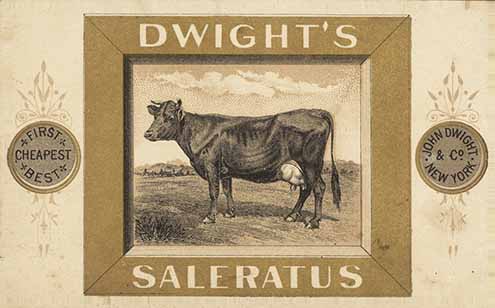

In 1876, John Dwight and Company is officially formed and uses the image of a cow as a trademark for Dwight’s Saleratus (photo #12; saleratus is Latin for aerated salt, another term for baking soda). Lady Maud, a prize-winning Jersey cow at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, is chosen as the image for the product, due to the popularity of using saleratus with sour milk in baking.

[12] Lady Maud gracing a trading card for Dwight’s Saleratus, which he later renamed Cow Brand (photo #13, item at Boston Public Library | Digital Commonwealth).

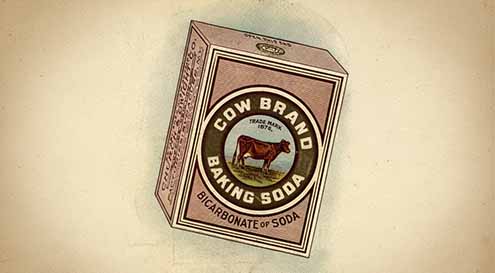

[13] Dwight’s Saleratus becomes Cow Brand (photo archive Duke University).

After Austin Church retired, his sons formed Church & Co. and introduced the Arm & Hammer brand with its famous logo, a symbol of the god Vulcan** (photo #14). Son James had used the logo at his prior company.

In 1896, the two companies joined to form Church & Dwight Co., Inc., unifying their baking soda businesses. For many years the Cow Brand and the Arm & Hammer brand were sold simultaneously. They were the same product with different branding. Both brands were equally popular, each with its own loyal following. The Cow Brand was phased out 1965.

[14] Vulcan’s arm and hammer, through the years (photo © Church and Dwight).

Today, commercial baking soda is primarily produced in two ways:

Mining the natural mineral form of sodium bicarbonate, now called nahcolite, and refining it using a simple water process. Most U.S. baking soda comes from large deposits—massive, underground evaporated lake beds of sodium carbonate in Wyoming, the world’s largest deposit. At current production rates, the reserves could last for more than 2,000 years.

Industrial synthesis (Solvay Process): Many manufacturers use the more efficient synthetic Solvay process, developed in 1861 by Ernest Solvay, a Belgian industrial chemist. It produces sodium bicarbonate from common salt (sodium chloride/NaCl), ammonia, and carbon dioxide. When salt is dissolved in water to form a brine, then treated with ammonia and carbon dioxide, it results in the precipitation of sodium bicarbonate.

THE HISTORY OF LEAVENING

For millennia before modern chemical leaveners arrived in the 19th century, bakers had only laborious, time-consuming methods to get dough and batter to rise.

Ancient Egyptians discovered around 3000 B.C.E. that dough left out would naturally capture wild yeasts from the air, causing it to rise and create lighter, airier bread. This sourdough method became the foundation of bread-making for millennia.

The Greeks and Romans refined these techniques. Sourdough starters were family treasures passed down through generations.

By the Renaissance (15th-16th centuries), beaten air was a major technique. Bakers would beat eggs vigorously, sometimes for an hour or more, to incorporate air bubbles that would expand during baking. This was exhausting work but essential for cakes and certain pastries.

By the 17th and 18th centuries, European and American cookbooks routinely featured cakes and light pastries that relied on beaten eggs. Recipes would often specify beating eggs “for an hour” or “until very light.”

By the 1700s, creating foam cakes and sponge cakes through egg-beating was common practice among those who could afford both the eggs and the labor (or servants) to do all that beating. The technique became even more refined in the 18th and early 19th centuries, with specific methods for beating egg whites versus whole eggs.

Ammonium carbonate became available as a leavening agent in the 17th century. Also called hartshorn or baker’s ammonia (hart is an old word for a stag), it was derived through the dry distillation of deer antlers, horns, and hooves. When heated, it released gases that leavened baked goods, but it left an ammonia flavor and smell that only dissipated in thin, crispy items like cookies, which is where it was focused. It entered into popular use in Europe by the 17th century, although the process was known to alchemists and apothecaries earlier. English and American cookbooks from the 1700s include recipes calling for hartshorn.

By the 18th century, hartshorn was fairly well-established in European baking, particularly in Germany and Scandinavia, where it’s still used today in some traditional Christmas cookies and other thin, crispy baked goods.

In the U.S., potash and pearlash and became the first chemical leavening agents to gain widespread use, in the late 1700s. Potash (potassium carbonate) was derived from wood ashes. They were placed in a pot, and water was leached through the ashes, after which evaporating the liquid in large pots produced alkaline salts.

Pearlash is a refined, purer form of potash. Starting around the 1790s, potash was further processed by baking it at high temperatures to remove impurities, resulting in a whiter, more concentrated product with a pearlier appearance. More importantly, the purification produced more reliable and predictable results for baking. It was dissolved in liquid and added to doughs for quick breads and cakes, and is credited as America’s first chemical leavening agent to gain widespread domestic use.

The U.S. became a major producer and exporter of both of these products in the late 18th century. The abundant forests generated plentiful wood ashes as a byproduct of clearing the land. Potash had many important uses‡ beyond baking, so even when pearlash took over that function, much potash was required for other everyday uses, fueling the American economy.

By the mid-19th century, baking soda (1840s) and baking powder (1850s) finally gave bakers reliable, shelf-stable chemical leaveners, replacing the need for patience, strong arms, and the luck of chemistry from nature. They engendered the “sour milk era” in the mid-to-late 19th century, when sour (fermented) milk or buttermilk‡‡ was combined with saleratus or baking soda to become a popular leavening method, particularly in American baking. (Before refrigeration, milk naturally soured relatively quickly, so households often had sour milk on hand. It became a useful ingredient rather than wasted food.) Early baking soda required an acid to activate it, so bakers needed to mix it with sour milk (which lactic acid) or molasses (lactic acid and other acids) to make their bread rise. Today, cream of tartar (tartaric acid) is added to baking soda in the factory.

Fleischmann’s yeast, created in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1868, was the first commercially reliable, compressed yeast cake. It was a leavener for yeast breads. Yeast bread uses a living microorganism (yeast) for a slow, biological fermentation that develops complex flavors, chewy texture, and airy crumb, unlike chemical leaveners (baking soda/powder) that provide a fast, one-time rise for quick breads, muffins, and cakes. By creating carbon dioxide gradually, requiring time for kneading and proofing, yeast builds gluten structure, and develops complex, tangy flavors and a chewy, airy crumb.

Think of all this the next time you bake cake or bread, buy it, or simply eat a piece.

|

________________

*A leavener (or leavening agent) is any substance, like baking soda, baking powder, or yeast, added to doughs and batters to produce gas (usually carbon dioxide) or steam. This makes baked goods light, airy, and voluminous by creating bubbles that expand during cooking. Leaveners fall into biological (yeast), chemical (baking soda, powder), or mechanical (whipped eggs, steam) categories, helping create a porous texture and desirable rise in foods.

**Vulcan (Greek: Hephaestus), one of the twelve Olympians, is the Roman and Greek god of fire and the forge. The son of Jupiter (Zeus) and Juno (Hera), and husband of Venus (Aphrodite) he is the mythical inventor of smithing and metal working. He was not just smith but architect, armorer, chariot builder and artist of all work in Olympus, the dwelling place of the gods. His forges were under Mount Aetna on the island of Sicily.

He produced Achilles’ armor and shield, Venus’s girdle, Cupid’s (Eros) arrows, Juno’s gold throne, Jupiter’s crown and lightning bolts, Mercury’s (Hermes) winged helm, the entire palace of Apollo and other gods, and intricate automatons (golden servants), among other marvels. He also created the first mortal woman, Pandora, from clay.

†Nahcolite, the mineral form of baking soda, forms in evaporated saline lake basins, similar to natron, often alongside trona and halite, in deposits from ancient, highly alkaline lakes. Particularly famous is the Green River Formation of Colorado, where it’s mined from oil shales. In modern mineralogy, natron, the form used by the ancient Egyptians, specifically refers to the pure mineral sodium carbonate decahydrate, while nahcolite refers to the pure sodium bicarbonate mineral.

††Other options for biscuits to rise: While baking soda requires an acid (like buttermilk) to react, baking powder contains both an acid and a base and reacts when it combines with liquid and again when it’s in the heat of the oven. You can even make old-fashioned “beaten biscuits” by physically beating air into the dough.

‡Potash had a remarkably wide range of uses and was a valuable commodity in early America and Europe. It was critical to glass manufacturing (both window glass and glassware), fertilizer, gunpowder production, soap-making, tanning leather, and textile production. It was used in various medicinal remedies and treatments, though the effectiveness of them is questionable by modern standards.

‡‡In addition to buttermilk, sour/fermented milk/dairy can include kefir, sour cream, and yogurt.

CHECK OUT WHAT’S HAPPENING ON OUR HOME PAGE, THENIBBLE.COM.

|