An Applejack Cocktail Recipe, What Is Applejack & Its History

|

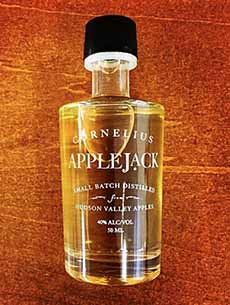

October is National Applejack Month, but we can’t remember the last decade in which we had some. We’ll remedy that today with three applejack cocktails, beginning with the Jack Rose (photo #1). Applejack is distilledd from hard cider. The cocktail recipes and the history of applejack follow, but first: Below: > The year’s 6+ applejack and cider holidays. Applejack is a type of brandy produced from apples (i.e., apple brandy). The U.S. government standards accord that applejack and apple brandy are the same thing. But applejack is different from the most famous apple brandy, Calvados from the Normandy region of France, to which it is often compared. The difference: Calvados is made from cider apples, whereas applejack is made from eating apples. Distillers can use: Applejack is directly related to apple cider; it is a strong alcoholic spirit made from hard cider, which is fermented apple juice. This happens through the process of either freeze-distillation (“jacking”—hence the name) or traditional distillation. Either process increases the alcohol content to make a much stronger drink than hard cider. Applejack has been associated with four presidents of the United States: But the first brand sold in America was Laird’s. The history follows. Craft applejack isn’t cheap—typically $40 or more per bottle—but it’s worth it. Do avoid the cheaper varieties made with bright-red artificial color and laden with artificial ingredients. Good grenadine—not the cheaper stuff—is essential to making good applejack. Tip: Think of applejack as a gift for a hard cider lover. Most people might thank that Bourbon was America’s first spirit, but applejack came first. Bourbon (1789), corn whiskey (moonshine) sometime in the mid-1700s*, and Tennessee whiskey (1825) came after. Popular in colonial times, applejack was often made at home until it began to be sold commercially. Applejack was once the nation’s most popular drink. America’s earliest cocktail may well have been the apple toddy (photo #10), which is applejack blended with boiling water and demerara sugar syrup [source]. Here’s a recipe, that also includes some sherry. It slipped from favor in the 19th and 20th centuries as other spirits grew in popularity—Bourbon and rum in the 19th century and gin, tequila, vodka and whiskey in the 20th. But at the beginning, in 1698, Alexander Laird, a County Fife Scotsman, emigrated from Scotland to America with his sons Thomas and William. William settled in Monmouth County, New Jersey. William probably was making scotch back in the old country, but here he turned his skills to using the abundant apples of the New World [source]. Apple brandy was first produced in colonial New Jersey in 1698 by William Laird, a Scots American who may have been a distiller in his Scottish homeland. Now run by the eighth generation of Lairds, until the 2000s it was the country’s only remaining producer of applejack, and continues to dominate applejack production. At the time the Laird family began to produce applejack, it was commonly produced at home from cider made after the apple harvest. It was consumed at home and shared with neighbors. Back then, Applejack was also imbibed in an unaged form dubbed Jersey Lightning [source]. The first commercial sales of Laird applejack was recorded in the family ledger in 1780. That year, after the war, Robert Laird incorporated Laird’s Distillery as the new nation’s first licensed commercial distillery [source]. However, perhaps because applejack is much less popular than other spirits, it is left off the list of the oldest licensed distilleries in America, much less the first! But in 1931, John Evans Laird received permission to produce apple brandy for “medicinal purposes” and stockpiled bottles applejack until the repeal of Prohibition in 1933. Then, the company was able to hit the deck running. Before 1968, applejack was synonymous with apple brandy. It was only when consumer preferences started moving towards lighter products like vodka and gin that applejack’s distinct identity took shape. The Lairds worked with the government to establish a new federal standard for blended apple brandy, and as a result, applejack is now defined as a blend of at least 20% apple distillate with neutral grain spirit that must be aged at least two years in oak [source]. In 1972 the Laird family launched the Blended Applejack spirit category, to meet meet consumer demand for lighter, lower proof spirits. Laird’s Applejack is now made from a blend of apple brandy (35%) and neutral grain spirits (65%). Modern applejack has a mellower flavor than original applejack. Laird’s is still the go-to brand, but today there are several craft distilleries making applejack. In the 2010s, a number of smaller craft distilleries began to produce applejack in colder climes: in Michigan (Coppercraft—photo #6), New Hampshire (Old Hampshire—photo #9), New York’s Hudson Valley (Cornelius——photo #7), and Pennsylvania (Eight Oaks—photo #8), among others. The name applejack derives from the traditional method of producing the drink, called jacking. It’s the process of freezing fermented cider and then removing the ice, increasing the alcohol content. See the next section to see how it was made. Applejack was traditionally produced from the hard cider that was the everyday drink for most Americans in the 18th century. Naturally fermented and low in alcohol, hard cider was safer than well water, cheaper than beer, and easy to make at home. Jacking was a low-tech method where spirits were distilled not by the usual method of heating, but by freezing. Any household with a supply of hard cider and cold weather could make applejack via freeze distillation. Cider produced from the fall harvest was left outside during the winter. Periodically the frozen chunks of ice which had formed were removed, thus concentrating the unfrozen alcohol in the remaining liquid. An alternative method involved placing a cask of hard cider in the snow, allowing ice to form on the inside of the cask as the contents began to freeze. Then, the cask was tapped to pour off the still-liquid portion of the contents. With each freeze, the water in the cider crystallized into slushy ice. Each time the ice was skimmed off, and the concentration of alcohol grew, until what is left in the barrel reached about 40 proof: the clear spirit that is applejack [source]. The alcoholic content rose from the fermented cider, at less than 10%, to 25% to 40% in the concentrated alcohol of applejack. Because freeze distillation was a low-cost method of production compared to evaporative distillation (which required a still and the burning of firewood to create heat for evaporation), hard cider and applejack were historically easier to produce—although more expensive than grain alcohol [source]. Modern commercially produced applejack is not produced by jacking but rather by blending two distilled spirits: apple brandy and neutral grain spirit. Perhaps the most famous applejack cocktail is the Jack Rose cocktail. It was created around the turn of the 20th century, and named for its rosy color (from the grenadine). Its origin is uncertain, but researchers peg it to either New York or New Jersey, likely made with Laird’s Applejack, made in New Jersey at the oldest licensed distillery in the U.S., established in 1698. The cocktail quickly found fans who enjoyed it until the advent of Prohibition. It was a favorite cocktail of John Steinbeck and was mentioned by Ernest Hemingway in “The Sun Also Rises.” (1926). It remained popular beyond 1948, when it was featured as one of six basic drinks to know in David Embury’s 1948 book “The Fine Art of Mixing Drinks” [source]. 1. COMBINE the applejack, lemon juice and grenadine in a cocktail shaker with ice. Shake vigorously until well chilled, 15 to 20 seconds. 2. STRAIN into a coupe glass, and garnish with a lemon twist. If you happen to have yellow Chartreuse and Benedictine, you can try this cocktail. Ingredients Per Drink 1. SHAKE all ingredients with ice. Strain into a chilled coupe glass. Ingredients Per Drink 1. SHAKE all ingredients with ice. Strain into a chilled coupe glass. |

|

|

|

THE YEAR’S 6 APPLEJACK & CIDER HOLIDAYS *Corn whiskey was first made sometime in the mid-1700s, by Scottish and Irish immigrants who were familiar with the whiskey-making techniques of their homelands. It was a rustic spirit that was not aged and mostly intended for immediate consumption [source]. The term “moonshine” comes from the fact that illegal spirits were made under the light of the moon, to avoid detection from authorities. They avoided paying the government tax on alcohol, which began shortly after the American Revolution [source]. CHECK OUT WHAT’S HAPPENING ON OUR HOME PAGE, THENIBBLE.COM. |

||