Mezcal, Tequila’s Smoky Cousin: The Difference

|

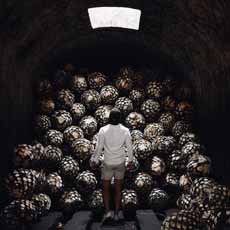

October 21st is National Mezcal Day. If you’ve heard of mezcal, you know it’s related to tequila. You may even have had some. But how does it differ from tequila? What’s the mezcal-tequila difference? Why should you buy a bottle of mezcal instead of tequila (or order a glass at your favorite watering hole)? Like the different whiskeys—American, Canadian, Irish, Japanese, and Scotch whiskeys— there are differences between mezcal and tequila, differentiated by the production process and sometimes by ingredients. In the case of tequila, both are highly restricted by law. This stems from a historic superiority, and the government’s desire to ensure the quality of Mexico’s most popular spirit and export. Distillation was invented by Greek alchemists in Alexandria, Egypt, in the second century C.E. The Arabs learned it from the Egyptians. The Spanish learned the art following the invasion of the Moors, around 800 C.E.† Cortez and his troops landed in what is now Mexico in 1519. After their brandy supply ran out, they looked for a substitute. They found that the Aztecs drank a beverage made from the juice of the agave piña, a drink called pulque (PULL-kay). It is still made today. Pulque is fermented like beer, but since it is not made from grain, it has “an acquired taste” to those brought up on barley beer. The Spanish didn’t wish to acquire the taste, so they taught the Aztecs the art of distilling the agave juice. Mezcal was born—the first spirit indigenous to the New World. The village of Tequila, established in 1656, focused on the mezcal trade, with mezcals of the time being called “tequila” after the town. The mezcal of that era was the equivalent of a bar drink, not the refined spirit it became. In fact, as agricultural and distillation processes evolved, it was determined that the blue agave plant, which grew well in the area of Tequila, produced the finest spirit. Over time, the vicinity (and later, the Mexican government) established rules protecting the name “tequila”—and commanding a premium price. Tequila and mezcal became legally separate products. Mezcal became the more affordable option; and while good mezcals were made, many inferior ones were made as well (like the brands with the worm in the bottle). |

[1] Celebrate with a glass of mezcal (photo courtesy Dos Caminos | NYC).

|

|

|

In recent times, with the growth of popularity of tequila—and of the finer aged tequilas—mezcal producers have upped their game. You can now find premium mezcals in the U.S. Some villages have devoted themselves to producing the best mezcals. ________________ *Agave (photo #3) is not a cactus; it is a succulent, and was once classified in the same botanical family as lily and aloe. Today it is classified in its own family, Agavaceae, which consists of more than 400 species. †Flavors and aromas, especially of finer spirits, are complex. While smoke may be a top note in mezcal, the particular flavor and aroma of any spirit (or wine, or craft beer) is predicated on a number of factors from the type of agave used, to where and how it was grown, to the production and aging processes. Each of these can vary widely. ‡Fractional distillation, a special type of distillation, was developed by Taddeo Alderotti, a Florentine physician who taught medicine in Bologna, Italy beginning in 1260. Fractional distillation is the separation of a mixture into its component parts, or fractions, such as in separating chemical compounds by their boiling point by heating them to a temperature at which several fractions of the compound will evaporate. This method is used today. (One of the first writers of medical literature, Alderotti is also credited with introducing the practice of teaching medicine at the patient’s bedside.) |

||