TIP OF THE DAY: Affordable Caviar

|

|

July 18th is National Caviar Day. When we looked into our purse, we decided we could not afford the “good stuff”: sturgeon caviar (prices* range from $123 to $349 for the rareat; prices per 30g/1.06 ounce).

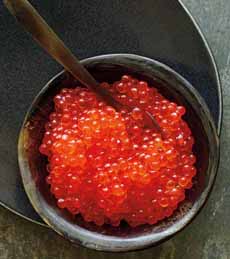

We couldn’t even afford sturgeon’s relatives, hackleback (a.k.a. shovelnose, $76/ounce) and paddlefish caviar ($32/ounce). That’s why we created a list of affordable caviar, below. But first… When the term is used by itself, “caviar” refers to unfertilized eggs (roe) harvested from any species of sturgeon. Caviar was first prepared by the ancient Chinese, from carp roe. The Persians learned the technique from the Chinese, and were the first to use the technique on sturgeon from the Caspian Sea. The word “caviar” comes from the Persian khavyar, from khayah, egg. It came into the English language in the 16th century. While “Russian caviar” has a global reputation as “the best” (some might vote for the lesser-known Iranian caviar), the Russians themselves do not call any fish roe caviar. They use the Russian word for egg, ikroj (pronounced EEK-ruh with a rolled “r”). In Japan, the Russian ikroj was transformed into ikura—the name by which it is ordered at sushi bars the world over. In the trade, the eggs of a fish are also called berries, grains and pearls. Once the roe has been salted it becomes caviar. However, the rising popularity of other types of fish roe in modern cuisine and the growth of the American hackleback and white sturgeon farming, have caused the definition of “caviar” to broaden. Today, the terms caviar and roe are interchangeable for consumers. Basically any fish egg is referred to as caviar; although in the U.S. only sturgeon caviar can be labeled simply “caviar.” Non-sturgeon caviars must be modified with the name of the fish (salmon caviar, whitefish caviar, etc.). |

|

|

A number of these more recently popular roes come from fish that are plentiful, like flying fish, trout and whitefish. This means affordable caviar. Their roe was not mainstream for decades. In many cases they were tiny, colorless, and/or marginally flavorful. But faced with the demands of the American palate, which has grown steadily since the rise of California cuisine in the 1980s, producers have rose to the occasion, to present caviar options that were both affordable and sustainable. Today there’s a broad choice of attractive and delicious roes. They taste like sturgeon roe as much as a meatball tastes like filet mignon. But most are very palate-worthy, and will expand your horizons. How much caviar should you buy? Well, you can get between 8 to 10 (1/2 teaspoon) servings per ounce of caviar. Figure at least 1/2 to 1 ounce of caviar per person. While this is a small amount, it’s enough for a tasting of different caviars. Buy what your pocketbook can afford. When we treat ourselves, we can eat a 7-ounce jar of salmon caviar or truffled whitefish roe as a garnish with dinner (yes, the whole jar). ________________ *Prices vary widely, depending on supply and demand, as well as the graded quality. For example, Tsar Nicoulai offers six different grades of American white sturgeon caviar alone, with prices ranging from $40 to $210, and everything in between. The highest-regarded retailers also charge more than other stores and e-tailers. You can find less expensive caviar online, but unless it is from a truly reputable vendor, you may be getting caviar that is old (there is no expiration date on caviar tins) or not what it is purported to be. Prices are stated in ounces, although European-based vendors like Petrossian use the European weight, grams. Since 30 grams equals 1.06 ounces, think of it as a wash. †Prices are provided for relative comparison. They were obtained from different websites, because we could not find one vendor who offered all or most of the options. Note that the price will also vary based on the amount purchased: A single ounce costs more than an eight-ounce jar or tin. Prices were in effect in July 2017. |

||

|

AFFORDABLE CAVIAR If you can’t afford $70 an ounce and up for sturgeon caviar, what are your choices? They’re on this list. We’ve provided Japanese names to reference the types most often found in sushi bars. |

|

|

|

Take care of the eggs. Caviar is very fragile and must be handled with care to keep the eggs from bursting. Caviar hates metal. Never touch a metal utensil of any kind to caviar: Metal oxidizes the roe and will make it taste metallic. Use a caviar spoon made of bone, tortoise shell, or mother of pearl. A plastic spoon works, too. Keep it cold. Caviar that is not shelf-stable (i.e., pasteurized) should be kept in the coldest part of the refrigerator (between 28 to 32°F.) Don’t freeze it! The caviar can last 15 to 20 days, unopened, in the fridge. Don’t open the caviar jar or tin until it’s ready to serve. Cover and refrigerate any leftovers promptly and use within a day or two. If caviar is left in the tin, the surface should be smoothed and a sheet of plastic wrap pressed directly onto the surface. Turn the tin over each day so the oil reaches all of the eggs. Here are more caviar tips.

|

||